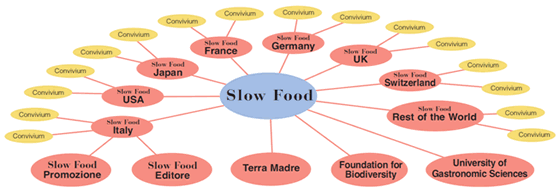

Figure 1: Structure of Slow Food International

Source: Malatesta, et al., 2007, p.11

Anette Kinley

Anette Kinley holds a BA in Sociology from the University of Calgary, and has worked as a researcher in the non-profit sector since her graduation. She is in the final stage of her MA-IS program, working to complete the final courses in her dual focus areas of Community and Equity Studies. Anette currently lives in Port Moody, BC with her husband and Boston Terrier, and works as a researcher at the UBC eHealth Strategy Office in Vancouver.

Academic research on the Slow Food movement has tended to focus on Western developed nations. Italy, in particular, has received the majority of attention as the birthplace of the official movement. However, the Slow Food movement has become a global phenomenon with local groups and projects on every continent. This article explores the global structure of the Slow Food movement and the similarities and differences between movements in developed and developing nations. It offers an in-depth comparative analysis of the Slow Food movements in Kenya and the province of Alberta, Canada, analysing the nature of local projects and the economic and cultural contexts in which they developed.

The analysis illustrates the close intersection of culture, identity and economy within the Slow Food movement. It also highlights the need to understand the movement not only as a “politics of consumption” – which the focus on Western nations promotes – but also as a “politics of production.” The global Slow Food movement encompasses the entire food system, from soil to table, as well as the cultural meanings and identities derived from all stages in the food process.

Keywords: social movement, slow food, developed world, developing world, food politics”

Over the course of human history, food has often become a political symbol in times of rapid social and economic change (Leitch, 2003). Examples include late 10th century revolts against the Italian monarchy in response to increased bread tax, and food riots in pre-Industrial England following the withdrawal of guaranteed prices on basic commodities for the poor. These types of actions are related to social and economic inequality, and the resultant inequality of access to food. However, “collective action around food [is also] often motivated by ideas of social justice within moral economies, rather than more pragmatic concerns such as hunger or scarcity” (Leitch, 2003, p.441). ‘Slow Food’, the contemporary food movement on which this article focuses, is an example of this type of approach. The Slow Food movement is multidisciplinary, taking a moral, social and economic stance on food production, distribution and preparation; it sees food as “not only a source of nourishment, but our history and identity, our culture and health, our land and our future” (Earth Markets, n.d.).

The Slow Food movement’s support of good, clean and fair food is a moral statement against the globalized, mass market food system which tends to dilute local food cultures and traditions (Schneider, 2008). It is a moral and political statement against the environmental unsustainability of the global food system, which is steadily displacing small-scale farming of diverse food varieties with monocultures produced through intensive industrial agriculture. It is an economic and social statement against the industrialized global food system, which marginalizes small producers and makes good quality food unaffordable or inaccessible to poor and marginalized people around the world (Schneider, 2008; Leitch, 2003).

From its beginnings twenty years ago, in a small Italian town, Slow Food has grown into a large and diverse global movement. In developed countries, the movement tends to be more consumption-oriented, while in developing nations the focus tends to be more on food production. This contrast between developing and developed countries reflects the roles of these areas in the global food system: people in developing nations are more likely to earn their livelihoods directly from agriculture; most people in developed nations are likely to have marginal connections to the process of food production. However, the truth is that we all eat, and our relationships to food are shaped by the cultures and traditions and the contexts in which we live.

For this reason, I argue it is more meaningful to look at the Slow Food movement in terms of the relationship between producers and consumers, rather than attributing its activities in different nations solely to economic status. The primary purpose of this article is to explore the structure of the global Slow Food movement and the various approaches to the movement across the globe.

I begin with a review of the literature on the Slow Food movement, and an exploration of the origins, purpose and structure of the movement. This is followed by case studies and a comparative analysis of the Slow Food movement in two settings – Kenya and Alberta, Canada – which represent the developing and developed world, respectively.

The Slow Food movement is most closely associated with the non-governmental organization Slow Food International (SFI, also referred to as ‘Slow Food’), which was founded in Italy in the 1989. The movement was sparked in reaction to late-capitalism's focus on increasing the speed and scale of economic growth and industrial production, and the resulting homogenization of food production, distribution, regulation and culture (Schneider, 2008; Parkins, 2004; Leitch, 2003; Miele & Murdoch, 2003). Slow Food International argues these changes have eroded the “territory” of food – the biological and cultural diversity associated with place – and weakened local food traditions (Schneider, 2008, p.389; Parkins, 2004; Leitch, 2003).

This erosion directly conflicts with Slow Food’s philosophy of food as of “not only natural ingredients but also cultural codes that govern its production, preparation, and consumption” (Schneider, 2008, p.388). This philosophy is the basis of the movement’s focus on creating change, at the level of personal and collective identity and practice (Bentley, 2001). Slow Food works to shift the act of eating from simply a personal act of nourishment and enjoyment to a democratic and political practice – a “politics of consumption” in “rejection of industrial agriculture and fast food” and in support of cultural, environmental and social diversity and sustainability (Leitch, 2003, p.456; Schneider, 2008, p.392). These goals are captured in Slow Food International's slogan: good, clean, and fair food.

... Good food is tasty and diverse and is produced in such a way as to maximize its flavour and connections to a geographic and cultural region. Clean food is sustainable, and helps to preserve rather than destroy the environment. Fair food is produced in socially sustainable ways, with an emphasis on social justice and fair wages (Schneider, 2008, p.390).

Though it offers a clear criticism of globalization, Slow Food is not an “anti-globalization” movement. On the contrary, Slow Food promotes “virtuous globalization,” in which communities engage in international exchange via the “pleasures of the table,” and “the food industry enact[s] the multiculturalism it so often champions”, by protecting the diversity of plant, animal and human cultures (Parkins, 2004, p.373; Schneider, 2008, p.397; Leitch, 2003). Rather than directly protesting the global food system, SFI (and the broader Slow Food movement) focuses its energies on creating local spaces for small-scale change and building relationships between individuals, communities, and local food producers (Schneider, 2008; Leitch, 2003). This positive, self-reflexive approach is referred to as “slow politics” (Schneider, 2008, p.395).

Over the past decade, consumer consciousness and demand for “culinary variation, flavour, goodness and health” has increased (Khare, 2008, p.153). Powerful players in the food system, such as the fast food industry, have begun to respond to these demands by moving away from global standardization to “continual diversification and localization” (Khare, 2008, p.153). The formation of economic networks between small farmers, community groups, and specialized food outlets also has become more common (Khare, 2008). The contribution of the official Slow Food movement to these shifts is unclear; however, increased consumer awareness of safety and nutritional concerns around mass-produced foods is a likely contributor to the demand for ‘slower’ food (Leitch, 2003).

One of the primary criticisms of the Slow Food movement is that its emphasis on the consumption of high-quality, and often high-priced products, made on a small-scale, excludes working class families (Pilcher, 2006). This reality has led others to propose that “food of moderate speeds,” or “good and healthy food, produced locally, for everybody,” is a more realistic vision for the global food system (Mintz, 2006, p.10).

The literature on food movements in developing nations tends to have a different focus. Terms other than “slow food” are used to describe similar movements, and the focus tends to be on food production, rather than consumption (Akram-Lodhi, 2007; Friedmann & McNair, 2008; McMichael, 2008). The impact on the globalized food system on farmers in developing countries is a common theme of food-related research on developing countries (Tuebal & Rodriguez, 2003). The food sovereignty movement, which seeks to re-establish farmers' autonomy over the production, distribution and marketing of their produce, is one such example (Akram-Lodhi, 2007).

This tendency in the literature does not mean, however, that the Slow Food movements in developing and developed nations are fundamentally incompatible. The strong relationship between food and identity applies regardless of geography or whether the people produce food, or only consume it (Bentley, 2001). Hernandez Castillo & Nigh’s (1998) study of a Mexican organic coffee growers’ cooperative and Gehlen’s (2003) study of Brazilian organic milk farms show that producers can see their agricultural methods as an expression of identity and a subversion of large-scale agro-industry. The case study of Kenya which follows also demonstrates that along with pragmatic issues of food production, distribution and pricing, Slow Food International projects in the developing world seek to preserve or revive local foods and traditions that contribute to identity.

While Slow Food International’s (SFI) activities do not capture the full extent of the ‘Slow Food’ movement around the globe, the mission, structure and membership of the ‘official’ movement give a valuable perspective to the aims and development of the movement as a whole. The mission of SFI has three main components: defending biodiversity, increasing awareness of food issues through taste education, and, creating a link between producers and co-producers (SFI, n.d.a). Slow Food’s mission has evolved over the years as the movement has grown and its leadership has learned from its expanding network of global partners. The release of the Ark of Taste – a registry of traditional foods at risk of extinction – in the mid-1990s marked a shift in the movement’s focus towards building relationships between food producers and consumers (Miele & Murdoch, 2003); this includes the aim of shaping disconnected “consumers” into engaged “co-producers” who identify with their role in food production (SFI, n.d.a).

Since its inception, Slow Food has gained a global following. At the end of 2009, the movement had over 100,000 members in 132 countries, national branches in 19 countries, and 1,000 local chapters around the world (SFI, n.d.b). As shown in figure 1, the structure of the global movement is complex: it is led by an elected executive council/board of directors and an international council comprising of representatives from countries which have more than 500 members (Malatesta, Mesmain, Weiner, and Yang, 2007). The majority of the work of the movement happens at the local level, through volunteer-driven groups called “convivium” (plural, convivia); national Slow Food associations coordinate activities in some of the countries in which the convivia are most active. Slow Food’s convivia are focused on cultivating the taste and food knowledge of the public, and building relationships among food producers and co-producers (SFI, n.d.b). While the convivia share these common goals, each one “is as unique as the region it’s in and the people, culture and food traditions there” (SFI, 2008c).

The SFI network also includes the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity (SFFB), which “supports projects around the world, ... [but focuses] on developing countries, where defending biodiversity not only means improving people’s quality of life, but can mean guaranteeing life itself” (SFFB, n.d. a).

The SFFB coordinates “presidia” projects which work with producers to:

The other body which executes the local work of Slow Food is the Terra Madre Network (TMN). Dubbed “the United Nations of food,” TMN is a network of small food producers, cooks and universities launched in 2004 (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a, p.42). The goals of Terra Madre(TM) are to:

The TMN is made up to two sub-networks: ‘food communities’, which are groups of small food producers and distributors who share common geographic area, culture or history (TMN, n.d.b); and, ‘chefs’, who are individuals who “dialogue and collaborat[e] with producers, and fight against the abandonment of cultural tradition and standardization of food” (TMN, n.d. c).

The way that membership in each of SFI’s local networks is distributed across the globe, brings some insight into how different countries have adopted the movement. As the birthplace and headquarter of the movement, Italy is the major player in all of Slow Food’s networks. Out of the 1,147 convivia in 100 countries across the globe, nearly 30 percent are in Italy (table 1). Likewise, Italy is the home of nearly 60 percent of all presidia projects, 23 percent of all Terra Madre food communities, and 17 percent of all Terra Madre cooks.

Table 1: Distribution of Slow Food Networks by Continent, 2009

|

Slow Food Convivia |

Slow Food Foundation Presidia |

|||||

|

Number |

Proportion |

Countries |

Number |

Proportion |

Countries |

|

Total |

1,148 |

100.0% |

100 |

302 |

100.0% |

48 |

|

Italy |

341 |

29.7% |

1 |

173 |

57.3% |

1 |

|

Europe (excluding Italy) |

352 |

30.7% |

35 |

70 |

23.2% |

20 |

|

North America |

194 |

16.9% |

2 |

7 |

2.3% |

2 |

|

Central & South America |

83 |

7.2% |

19 |

30 |

9.9% |

9 |

|

Africa |

59 |

5.1% |

19 |

11 |

3.6% |

7 |

|

Asia |

74 |

6.4% |

22 |

11 |

3.6% |

9 |

|

Oceania |

45 |

3.9% |

2 |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

|

|

Terra Madre Food Communities |

Terra Madre Cooks |

|||||

|

Number |

Proportion |

Countries |

Number |

Proportion |

Countries |

|

Total |

1,688 |

100.0% |

144 |

739 |

100.0% |

105 |

|

Italy |

387 |

22.9% |

1 |

128 |

17.3% |

1 |

|

Europe (excluding Italy) |

366 |

21.7% |

38 |

258 |

34.9% |

36 |

|

North America |

219 |

13.0% |

2 |

143 |

19.4% |

2 |

|

Central & South America |

255 |

15.1% |

23 |

71 |

9.6% |

14 |

|

Africa |

208 |

12.3% |

38 |

56 |

7.6% |

23 |

|

Asia |

221 |

13.1% |

35 |

69 |

9.3% |

26 |

|

Oceania |

32 |

1.9% |

7 |

14 |

1.9% |

3 |

|

Sources: SFI, n.d. b; TMN, n.d. b; TMN, n.d. c

When the network members from the rest of Europe are considered separately from Italy, some interesting trends appear. The Convivia network is dominated by Europe and North America, as is the Terra Madre cooks network. Europe dominates the Presidia network, with Central and South America as a distant second. The Terra Madre food community network breaks the trend of European and Italian dominance, with Africa, Central/South America and Asia more equitably represented. African food communities, for example, make up 12.3 percent of all TMN food communities.

Despite the dominance of European and North American branches of the movement, Slow Food projects across the globe are diverse and responsive to local contexts. The movement’s leadership is highly conscious of using a non-Eurocentric approach suited to the local context of each branch (SFI, 2007). As the following case studies show, the global distribution of the SFI networks is a reflection of the social, economic and cultural contexts of each country or region.

In terms of its economy, Kenya has many of the characteristics typical of a developing nation. Over 70 percent of Kenyans work in agriculture, most owning small plots of land, called “shamba,” and working as casual farm labourers (SFI, 2009b; Brevet, 2009). Agriculture is the source of half of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which totalled $US 1,640 per capita (purchasing power parity) in 2007 (SFI, 2009b; The Economist, 2008). Kenya's Gross National Income (GNI) in 2007 was $US 680 per capita (UNICEF, n.d.); in some regions of Kenya, families survive on less than $US 600 per year (SFI, 2009b). In 2007, just one in five Kenyans lived in urban areas (UNICEF, n.d.).

Like many developing nations, traditional crops have been supplanted by monocultures as a result of global competition and market demand; this has had an additional impact on farmers, who are less likely to get a fair price for traditional crops and food products (Pilcher, 2006, p.77). Millet and sorghum were traditionally the core of the Kenyan diet; the cultivation of these crops has been overtaken by large-scale farming of crops such as maize, wheat, potatoes and coffee (Brevet, 2009). While farmers may grow traditional varieties of food on their shamba, it is estimated that 90 percent of Kenyans now rely on maize as their staple diet (Brevet, 2009).

The shift to monoculture crops has had a marked impact on Kenya’s biodiversity; it is estimated that only 30 of more than 200 indigenous crops are currently being cultivated (Brevet, 2009). Of particular concern is that some of the non-indigenous crop varieties, including maize, are not drought-resistant (Cravero, 2009). This has had significant consequences for the country, as multiple years of drought have resulted in wide-spread crop failures and hunger (Cravero, 2009). The problems of drought have been compounded by low government investment in small-scale agriculture and recent political upheaval. These factors have created a food crisis, and led to a push by the government for Genetically Modified (GM) crops and more intensive agriculture (Cravero, 2009). Increasing the reliance on intensive agriculture would further marginalize small producers, who cannot afford the expense of the seeds, fertilizers and other technologies required; further, the reduction in drought-resistant indigenous crops would also make the country more vulnerable to crop failure (Cravero, 2009).

The shift to monoculture crops has also contributed to the erosion of local food culture and practices in Kenya (Kariuki, 2009; Brevet, 2009). This change in food habits has resulted in the widespread loss of knowledge regarding indigenous foods and traditional agricultural practices, as well as a loss of pride in Kenya’s traditional food culture (Brevet, 2009).

Kenya is one of the leading countries within the Slow Food movement in Africa. A Kenyan representative was elected to the SFI executive committee in 2007 and, as of 2009, the country had 140 Slow Food members, ten Convivia, 21 Terra Madre food communities, and five of Africa's 56 Terra Madre cooks (SFI, 2007; SFI, 2009; SFI, n.d. b, TMN, n.d. b; TMN, n.d. c). In addition, recent research conducted through Kenya’s Convivia has identified a number of food products that could be included in Slow Food’s Ark of Taste or developed into new Presidia projects (Kariuki, 2009).

Slow Food initiatives in Kenya have been working to address the cultural, ecological and nutritional challenges that Kenyans face. Kenya's food communities include: five groups that breed varieties of sheep, goats and cattle; twelve groups that cultivate seeds, vegetables or grains; two groups of beekeepers; one palm wine producer; and, one group committed to preventing soil erosion caused by intensive agriculture (TMN, n.d. b). These communities are primarily focused on preserving traditional foods and sustainable farming methods, providing food to local communities, and passing down knowledge of indigenous foods and farming techniques to the younger generations (SFI, 2008b; TMN, n.d. b).

The Kenyan Convivia are primarily engaged in activities to teach youth about Kenya's traditional foods and farming methods. School garden initiatives are at the forefront of Kenya's Convivia activities, with 11 school gardens reaching over 400 students (SFI, 2009b). The Convivia see school gardens as a long-term solution to the growing shortage of farm labour that has resulted in part from the lack of emphasis on agriculture in school curricula (SFI, 2009b). Classroom gardening activities expose students to indigenous crops and give hands-on experience with sustainable cultivation practices that would help them to be successful as small-scale farmers (SFI, 2009b; SFI, 2008a); the students can also take pride in tasting their harvest as part of their school's daily lunch menu (SFI, 2008a). The Kenyan Convivia network also engages with government officials and local NGOs, meeting with them to share the work of the Convivia and to discuss issues related to food production and distribution (Malatesta, et al., 2007).

Due to the expansive geography of Canada, I have chosen to focus this case study of the developed world on Alberta – the province in which I was raised. Alberta's economy is one of the strongest in North America. In 2007, Albertan families earned a median after-tax income of $75,300 per year – significantly higher than the Canadian median of $61,800 (Government of Alberta (GoA), 2009). Agriculture is the source of just 1.9 percent of the Alberta's GDP, which totalled $ 74,825 [1] per capita in 2007 (GoA, 2009; Carrick, 2008). Just three percent of Albertans work in agriculture, a slightly higher percentage than for Canada as a whole (2%) (Statistics Canada (SC), 2009a; SC, 2009b). In 2006, 18 percent of Albertans lived in rural areas – 2 percent less than the Canadian average (SC, 2009c).

There are over 10,000 companies (including farms) in the agriculture industry in Alberta, approximately 8,000 of which are directly involved in food production or processing (Manta, n.d.). Alberta’s core food products include beef, canola, flax and wheat (GoA, 2008). Like most industrialized nations, much of Alberta's agricultural activity is controlled (directly or indirectly) by large multinational corporations and heavily influenced by international commodity markets. Beef producers, for example, experienced two decades of consolidation in the meat-packing industry, which is now primarily controlled by two US companies, Cargill and XL Foods (Phillips, 2009). Today, approximately 80 percent of all Canadian beef is processed in Alberta at two meat-packing plants, and about 40 percent of domestic beef production is exported to the United States (Phillips, 2009). This consolidation, and the accompanying reliance on the US market, has had a significant impact on ranchers, who are fetching half the average price per steer than 40 years ago – the lowest price since the Great Depression (Phillips, 2009). This situation has been compounded by recent years of drought, which significantly increased the price of feed, as well as the BSE (mad cow disease) crisis, which led to a two-year closure of the US market to Canadian beef (Phillips, 2009).

These factors have led to continually decreasing profit margins for cattle producers, making it difficult for small-scale farms to remain viable; ranchers have been pushed to reduce their herds, consolidate or sell their land to large feedlots or meat-packing companies (Phillips, 2009). The rising average age of the Alberta farming community – 55 years in 2009 – is an additional threat to the longevity of small-scale, family-run agriculture in the province (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a).

The threat to small farms in Alberta is not only an issue of economics. Continuing with the example of the cattle industry, ranching has been a central part of Alberta's culture since it was settled; multiple annual agricultural fairs and rodeo events across the province, and Albertans’ pride in the quality of the province’s beef – are evidence of Alberta's ranching and cowboy culture (Calgary Stampede, n.d.; Canadian Finals Rodeo, n.d.). The gradual disappearance of small-scale ranching conflicts with this aspect of the Albertan identity.

Alberta is home to two of Canada's 39 Slow Food Convivia, and has 250 members across the province (SFI, n.d. b; Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a); it is also home to the Red Fife Wheat Presidium, Canada's only SFFB project (SFFB, n.d. b). Alberta's presence in Canada's Slow Food community is strongest in its involvement in Terra Madre; the province has fifteen of Canada's 43 food communities, and ten of the country's 47 TM chefs (TMN, n.d. b; TMN, n.d. c).

The Slow Food initiatives in Alberta are focused primarily on: sustainable food production and distribution; public education; the promotion of local food products and culture; and the production of quality artisan food products. Of the fifteen Terra Madre food communities in the province, seven raise livestock and produce meat products (including bison, turkey, lamb and beef) and six grow vegetables or grains. There is also one community of beekeepers who produce honey and other bee products, and one community of artisan bakers who use locally grown and milled flour.

Terra Madre chefs in Alberta have taken a very active role in the Slow Food movement, viewing themselves as stewards of slow food production and consumption (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a). One Calgary chef has built relationships with 40 to 50 local producers, who supply his restaurant with seasonal products; another has organized workshops and conferences to educate the public and bring together local producers and consumers (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a). The Calgary and Edmonton convivia are also active in public education activities, organizing events and promoting local products at farms and restaurants around Alberta (Slow Food Calgary, n.d.; Slow Food Edmonton, n.d.).

The philosophy of eating locally to support small-scale, sustainable agriculture is a dominant theme of the Slow Food movement in Alberta (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a). The argument is that quality, affordable local food, benefits both consumers – who know where the food they're eating comes from and how it is produced ; and producers – who will be better able to survive financially if local consumers buy their products at fair prices (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009b). Buying local thus becomes a way of improving the sustainability and security of the food system and the economy. Equally important is the emphasis on buying local and taking pleasure in preparing and eating food as a way of making a political statement regarding one’s beliefs and values (Hobsbawn-Smith, 2009a).

In addition to the official Slow Food movement in Alberta, there are many other initiatives that promote sustainable agriculture and the consumption of local food products. Alongside the more than 100 “Alberta Approved” Farmers' Markets across the province, Community Shared Agriculture (CSA) an initiative which forms direct partnerships between small-scale producers and consumer households – has gained momentum in recent years (Agriculture and Rural Development (ARD), 2009b; ARD, 2009a). A group of Edmonton businesses have started an initiative called 'Eat Local First' to educate the public on the benefits of eating locally, and promote small businesses which support local, sustainable agriculture (Keep Edmonton Original, n.d.). These are but a few of the initiatives happening beyond the official work of SFI’s local branches, representing the movement towards 'slow food.'

While Kenya and Alberta are worlds apart in terms of socioeconomic profiles, there are a number of important similarities between the two, both in terms of economic pressures and the focus of the Slow Food movement. Firstly, farmers in both Kenya and Alberta face pressures from industry and government to intensify agriculture through the use of technologies and monoculture crops that have potential for greater yields. This industrial strategy leaves both countries at greater risk of crop failure and food production shortages as a result of poor weather and other factors beyond farmers’ control (Brevet, 2009; Cravero, 2009; Akram-Lodhi, 2007). However, this pressure is arguably much more intense in Kenya, given the extent of poverty and hunger in the country, as well as the centrality of agriculture to its economy.

Secondly, Kenya and Alberta also face the dilemma of an aging farming population. The lack of emphasis on agriculture in school curricula, as well as the decreasing profitability of small-scale farming, has made agriculture a less attractive or feasible career choice for younger generations (Pilcher, 2006; Phillips, 2009). The consequence of this trend, if it continues,would be a continuous increase in the percentage of food supplied by industrial agriculture.

In terms of the activities of the SFI movement, the networks in both countries emphasize the importance of small-scale producers receiving a fair price for their products. Both movements also promote the use of natural and environmentally sustainable farming techniques. Finally, the Kenyan and Albertan movements both have elements which promote local food culture; this issue is perhaps of more importance in Kenya, where the threat to local food traditions appears to be more acutely felt, and where agriculture is the mainstay of the economy.

These case studies also reveal some important differences in the focus of the Slow Food movements in Kenya and Alberta. Based on the descriptions of the Terra Madre Food Communities, it appears that the Slow Food movement in Kenya is more focussed on the production of food for the communities’ own sustenance, with only surplus food being sold outside the community. In contrast, Alberta producers in the movement are more focussed on producing food for sale, rather than for their own consumption. In addition, Slow Food in Kenya is more about sustaining or reviving the production of indigenous varieties of plants and livestock. While this is also a concern in Alberta – as shown by the Terra Madre bison ranching communities and the Red Fife Wheat presidia – it is not as central to the work of the movement.

Another apparent contrast is that Slow Food in Alberta has a much stronger orientation towards consumers. Many Slow Food projects in the province are concerned with teaching consumers about the benefits of local, sustainable food; they also tend to emphasize food purchasing decisions as statements of values and identity. The Albertan movement also tends to more closely reflect the SFI philosophy of enhancing the pleasure of preparing and eating food. While the Slow Food movement in Kenya does focus some of its work on consumers – such as its gardening projects in schools and urban areas – the emphasis is much more centred on the experience and knowledge of food producers.

These differences appear to be mostly an issue of the economic structure and position of the two countries. In Kenya, the economic dominance of agriculture, regular recurrence of drought and critical food shortages, and limited after-tax household income of the population result in an emphasis on food production over consumption. The opposite is true for Alberta. The comparative wealth of the population and the small proportion of people working in agriculture make consumers the natural focus for Slow Food activity. It is through their food purchasing choices that most Albertans are able to influence how their food is produced. For Kenyans, who are more likely to be closely connected to agriculture, choices regarding the foods they produce, and how they do so, are the most effective way to influence the food system.

The criticism that the Slow Food movement is not accessible to many working-class people is true, in part; foods produced “slowly” can come with a premium price that lower income families cannot afford, thereby excluding them from participation in the “politics of consumption.” However, the case studies presented demonstrate that the Slow Food International movement is decidedly not just about the pleasures of eating. It concerns the processes of the entire food system, from soil to table. It even extends beyond the physical food products and meals to the cultural meanings and identities derived from all stages in the food process.

The understanding of slow food as a “politics of consumption” has contributed to an imbalance of research on the movement, with the majority of literature focused on Western, developed nations. It has also created an artificial dichotomy of developed nations as consumers and developing nations as producers. Research on food movements tends to focus food production in developing countries, and food consumption in developed nations. This is serious oversight, as there is a rich variety of slow food activity occurring in developing nations around the globe.

It is undeniable that people in developing countries tend to be more deeply involved in food production, and those in developed nations are more exclusively involved in food consumption. This reality has shaped the development of the SFI movement (as well as the broader Slow Food movement) across the globe. However, the movement cannot be neatly divided into developing and developed world initiatives. While the pressures felt by producers in different regions vary, all producers face the general pressure of agricultural intensification; and, while the social and economic contexts of consumers around the globe also differ greatly, all consumers have become distanced (to varying degrees) from the food production process. The commonality of these challenges across the local contexts in developing and developed nations makes it more appropriate to think of slow food initiatives in terms of their relative consumer- or producer- orientation.

The partnership between consumers and producers makes Slow Food not just a “politics of consumption,” but also a “politics of production.” To look at Slow Food without recognizing both of these “politics” would be to see an incomplete picture of this diverse global movement. Slow Food International recognizes the shared role of producers and consumers in resisting the dominance of large-scale industrial agriculture and homogenization of food culture. Thus the concept of the “co-producer” – the aware and engaged consumer supporting the work of local food producers – bridges the divide between producers and consumers.