Anjela Godber

This qualitative analysis compares multiple-choice and open-ended questionnaires from women cyclists in Vancouver, British Columbia to evaluate the gender differences in cycling behaviour within the city. Using grounded theory methodology, responders described a wide array of gender-influenced cycling patterns. Differences in women’s cycling motives and deterrents varied with perceptions of physical and emotional safety, the destinations and expected appearance, amount of household errands, fear of bicycle theft, and whether the purchase of an e-bike was economically viable. While some incentives for cycling could be attributed to both men and women, several motivations and deterrents were gender-biased . One of the predominant issues for determining gendered experiences in community spaces like cycling routes, is the perception of fear. Women responders often shared situations of aggressive behaviours from both drivers and cyclists as a significant impediment for cycling. The data revealed that perceptions of emotional and psychological well-being had a significant influence on women’s cycling behaviours . Research on gender and cycling has often found that perceptions of safety have had a significant impact on rates of women cyclists. However, safety is often categorized as feeling physically safe and separated from vehicles. This research has found that perceptions of emotional and psychosocial safety also have an impact on the gendered experiences along cycling routes. To increase the rates of female cyclists and achieve gender-balanced cycling behaviours, it is essential to consider the differences in the gendered experiences of community spaces. Perceptions of safety, belonging, and inclusion will often differ between men and women. Municipalities will need to consider diverse and inclusive use of space; and integrate gendered perspectives along cycling routes.

KEYWORDS:Gendered cycling, cycling safety, women and cycling, gendered community spaces

The relationship between women and cycling has been rooted in social justice, in the questioning of conventional gender roles, and the forward momentum of the suffragette movement (Hanson, 2010). "The New Woman" was the term used to describe modern women who challenged convention by drastically changing their clothing style to accommodate cycling, developed a sense of control over their bodies and behaviours, and participated in political campaigning (Zheutlin, 2005). In 1896, suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony commented that the bicycle "has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. " (Zheutlin, 2005, p. 5). In many countries, the bicycle has continued as a symbol of independence, freedom, autonomy, and mobility (Sainath, 2017). Many countries in Europe, such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium, experience gender-balanced cycling with women accounting for 49%-55% of bike trips (Bopp, Child, & Campbell, 2014). Unfortunately, in the U.S and Canada, the rate of cycling behaviours is sharply skewed, with females only accounting for 20-25% of cyclists (Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals, 2016; Hanson, 2010).

To better understand the gender gap in cycling, it is essential to consider personal experiences, travel behaviours, and women cyclists' motives and deterrents. Much of the research on gender and cycling has identified that separated bike lanes are the most significant determinant of cycling increases amongst women (Akar et al., 2013; Winters et al., 2011). However, Vancouver researchers have found that 39% of cyclists using separated bike routes were women (BC Climate Action Toolkit, 2016.). This rate is still less than half of the number of male cyclists. As the City of Vancouver has the protected cycling infrastructure identified as a feature for increasing the rates of female cyclists, consideration of other factors and initiatives needed to create gender-balanced cycling behaviours must be explored (Akar et al., 2013; Winters et al., 2011). While reviewing research on motives and deterrents for women to cycle, I realized that many of the studies on cycling and behaviour did not explore the gender differences in the perceptions of safety and its impact on cycling patterns and access to cycling opportunities (Damant-Sirois & El-Geneidy, 2015; Mertens et al., 2016; Winters & Cooper, 2008; Winters et al., 2011). Analysis of motives and deterrents through qualitative studies, allowing women to share their experiences, provide an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of a woman's perspective of cycling in the City of Vancouver (Woods, 1999).

In 2019, I conducted a grounded theory research project on Women and Cycling in the City of Vancouver. This qualitative research asked women to share their experiences, motivations and deterrents to cycling in the City (Woods, 1999). The interest in the study exceeded my expectations, and further analysis of the research responses was needed. This secondary research study provided an opportunity to delve into each participant's individual stories and narratives describing what has shaped their cycling behaviours. These experiences provide the following information

Analysis of the data obtained through the grounded theory research revealed that differences in women's cycling motives and deterrents varied with their perceptions of physical and emotional safety, the destinations and expected appearance, amount of household errands, and fear of bicycle theft. While some incentives for cycling, such as exercise and easy parking, could be attributed to both men and women, other reasons may be more gender biased. Women responders had expressed experiencing several aggressive behaviours from both male drivers and male cyclists that accounted as a substantial impediment for cycling.

The data predominantly depicts emotional and psychological connections to cycling as strong motivators while feeling threatened or intimidated as significant deterrents. Women may experience higher rates of emotional and psychosocial connectivity while cycling, which may also influence what deters them from cycling. Perceptions of safety is certainly a predominant force that shapes a woman's decision to ride a bike, but safety is not just a physical matter; it must also include perceptions of emotional and psychological safety.

This secondary research paper is a further examination of the original data obtained in the grounded theory research. This examination includes identifying the predominant motives and deterrents of cycling behaviours while considering the differences in how men and women may use community spaces (Day, 2011; Foran, 2013). The literature review determined what gaps may be present in the research on women and cycling. This study aims to share actions that various levels of government can take to improve gender-balanced cycling behaviour by mitigating psychological intimidation and threat. These action items could potentially be shared amongst other municipalities across the country by disseminating the data and research findings.

The question of motivations and deterrents for women and cycling in the City of Vancouver first began when I read an article describing women and cycling behaviour. The research, "Bicycling Choice and Gender Case Study: The Ohio State University," looked at gender differences in cycling behaviours and travel patterns on college campuses (Akar et al., 2013). The research points out that although men and women experience similar environmental opportunities and constraints, their perceptions of the safety and feasibility of cycling differ (Akar et al., 2013). The researchers found that women are more sensitive to being close to bicycle trails and paths (Akar et al., 2013). The paper suggested that different policy and infrastructure changes may be required to encourage more women to bicycle (Akar et al., 2013). This study motivated me to think about gendered cycling behaviour in Vancouver, especially considering the growing network of separated bike lanes.

I decided to predominantly focus on cycling research based in the U.S and Canada as cycling rates are still comparatively low and gender-imbalanced than to those of many European countries. According to a Translink report, in 2008, 72% of cyclists in the Metro Vancouver Region were men, and only 28% were women (Translink, 2011). In many European countries, rates of cycling for women can vary between 48%-60% (De Geus et al., 2008; Mertens et al., 2016; Translink, 2011). While reviewing the diverse array of research articles on cycling behaviours, various themes emerged:

A significant amount of research on cycling behaviours does not consider gender differences in the uses of cycling infrastructure, or the motives and deterrents to cycling. Vancouver area research on the motivators and barriers of bicycling have identified the importance of the location and design of bike routes to improve cycling behaviours (City of Vancouver, 2019; Winters et al., 2011; Winters et al., 2016). In a 2010 study, Vancouver-based researchers describe the strongest motivators for cycling as safe bike routes away from traffic, relatively flat surfaces and aesthetically pleasing environments (Winters et al., 2010). The highest deterrents were unsafe surfaces and proximity to traffic (Winters et al., 2010). While the study identifies the high percentage of male participants, it is unknown how gender might factor into the motives or deterrents for cycling behaviour.

Similarly, a 2011 cycling study by Translink mentions the goal of increasing women cyclists in the Metro Vancouver region but does not consider gender-based action plans to achieve this (Translink, 2011). Gender rates are also unknown in a 2015 study of how cycling networks serve residents in various cities across Canada (Vijayakumar & Burda, 2015). While this study considers how safe cycling infrastructure has contributed to a growth in cycling, there is no mention of cycling rates amongst men vs. women (Vijayakumar & Burda, 2015). It is unclear if bicycle infrastructure has led to an increase in the rate of women cyclists in Canada. The Metro Vancouver Regional District and UBC have released various articles and reports on cycling behaviours with little discussion of the differences in gendered behaviours (Jaffe, 2015; Wilkins & Service, 2019; Winters et al., 2016).

A significant amount of research on gender and cycling behaviours have identified that separated bike lanes are the most significant determinant for increases in cycling amongst women (Akar et al., 2013; Bonham & Wilson, 2012; Damant-Sirois & El-Geneidy, 2015; Le et al., 2019; Teschke et al., 2017; Winters & Teschke, 2015; Winters et al., 2011). Perceptions of physical safety is a significant factor in shaping a woman's decision to ride a bike. According to a 2010 Women's Cycling Survey, most responders mention quality cycling infrastructure, such as separated bike lanes, as a high motivator for cycling (Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals, 2016). Similar findings were reported in a 2010 Metro Vancouver study that found significant gender differences in the choice of routes that cyclists were willing to take, based on safety (Winters & Teschke, 2015). Most of the studies have identified that since women are more "risk-aversive" than men, this may explain the gender differences in cycling behaviour (Bonham & Wilson, 2012).

Perceptions of safety often refer to physical safety and community-based supports while cycling. Some research studies have considered how supportive social networks can encourage women to cycle (Bopp et al., 2014; Lee, 2016). In the study, Embodied Bicycle Commuters in a Car World, D. Lee presents a thought-provoking examination of how the sensory experiences of cycling can be highly motivating (Lee, 2016). Bopp et al. have also considered how positive social connections can encourage many women to cycle. The researchers mention a few studies that attribute social supports from family and friends and supportive community policies as directly contributing to cycling behaviours (Bopp et al., 2014). While the Bopp et al. research addresses various physical, social, environmental, interpersonal, and community-based motives for cycling, I wondered how these factors played a role in women and cycling behaviour in a city such as Vancouver.

In 2015, the City of Vancouver released its Walking and Cycling in Vancouver Report Card (City of Vancouver, 2015). This report is a brief discussion of how one separated bike lane has seen an increase in the rate of women cyclists. The Hornby bike lane in Downtown Vancouver is featured as an example of how before the separated bike route, 28% of cyclists were women; after constructing the protected bike lane, 39% of cyclists were women (Vancouver, 2015). This study does address how separated bike lanes can improve the rate of women cyclists (Vancouver, 2015). However, there is still a significant gender imbalance on an easily accessible, separated route that encompasses safety and community-based supports, motivating factors identified by many research studies on gender and cycling. If the City of Vancouver has the cycling infrastructure and a supportive sense of community to increase the rate of female cyclists, what other factors and initiatives are needed to create gender balanced cycling behaviours?

Feminist geography and qualitative analysis can contribute to an improved understanding of the gender gap in cycling by considering lived experiences, cycling preferences, and women cyclists' travel behaviours. In the 2011 article, Material Matters: Gender and the City, author Brenda Parker provides a literature review of gender and urban planning and explores how women experience the built environment in very different ways than men (Parker, 2011). These gendered experiences can shape perceptions of fear and safety (Parker, 2011). Perceptions of safety and neighbourhood image have also been addressed in a 2019 article on the gender differential in the awareness of community safety (Zavattaro, 2019). In this paper, researchers suggest that urban planners and policymakers should consider feminist ideas when designing healthy neighbourhoods (Zavattaro, 2019). Author Kirsten Day also explores how the design of urban areas have neglected women's needs and lived experiences. She calls for changes in urban design to create more equitable cities for women (Day, 2011). The gender differences between how men and women use community infrastructure, including separated cycling routes, needs to be addressed and better understood through qualitative research highlighting women's lived experiences on a bicycle.

Qualitative studies, allowing women to share their experiences and their stories, provide an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of a woman's perspective of cycling within urban areas, such as the City of Vancouver (Woods, 1999). A recently reported qualitative study has considered mothers and cycling and how issues surrounding the mobility of care can influence a woman's decision to ride a bike (Sersli et al., 2020). This particular study was completed in Vancouver and utilized interviews to learn more about women's, or more precisely, mothers’ experiences with cycling in the city after they had completed a cycling course (Sersli et al., 2020). This study found four themes to the interview data that centred around the values of cycling and parenting, the skills of cycling with or without children which they had learned through the cycling course, cycling infrastructure such as separated bike lanes, and time constraints due to household errands (Sersli et al., 2020). The interviews were fascinating to read. Many of the women in my research shared similar cycling experiences with their children and expressed how cargo bikes and safe cycling routes enhanced their ability to bike. While this study addressed an aspect of women and cycling that many other research reports had not considered, there were still areas that I wanted to explore for increasing gender balances in cycling behaviour within the City of Vancouver.

The data for this secondary research project has been adopted from a grounded theory research paper that was completed in October 2019. The qualitative research design guided by grounded theory methods allowed for an in-depth analysis of female participants' meaning and processes attributed to cycling. It presented an opportunity for developing a holistic understanding of the gender differences in cycling behaviour. The stories and shared experiences provided discovery of critical discourses and nuances of women's experiences with cycling that might be less visible in quantitative cycling behaviour studies.

The qualitative-based questionnaire addressed women and cycling behaviours, including motivators, deterrents, and personal stories. The form also queried the first three digits of the responders' postal code to ensure a diverse geographical representation. Age range was also requested to consider if that potentially played a role in cycling behaviours. In total, responders answered eight questions with six directly addressing their motive and deterrents for cycling:

While most of the questions relied upon open-ended responses, two of the questions did provide a set of options based on the reviews of research findings on gender and cycling. In the journal articles, women were most often found to participate in recreational cycling and expressed concerns about physical safety, too many household errands, and policies around professional work attire (Bopp et al., 2014; Le et al., 2019; M. et al., 2012; Parker, 2011; Sersli et al., 2020; Zavattaro, 2019). It was essential to include questions pertaining to previously identified factors to consider if a cycling-friendly City such as Vancouver also experienced similar gender-specific motives and deterrents.

The survey provided respondents with a set of choices for questions 4 and 7; there were also opportunities to share experiences and stories that may not necessarily fall into a set category. Questions 3, 4e, 6 and 8 provided opportunities to share information and experiences using open-ended questions. These experiences inspired the development of the theory that perceptions of emotional and psychosocial safety impact a woman's motives and deterrents for cycling and, therefore, may factor in the gender imbalance of cycling behaviours. Some women in the study had also shared frustration over the lack of way-finding signs and poorly maintained and designated cycling routes that abruptly ended. While these issues may not necessarily be gender-based, they certainly contribute to cyclists' safety and send a clear message to vehicle drivers that they are entering a cycling-centred area.

This secondary research paper is a further investigation of my query, "If the City of Vancouver has the safe infrastructure, beautified cycling routes, direct access to destinations and general acceptance of cycling culture, why is there still a gender imbalance in cycling behaviour?". Examining this question would entail asking women cyclists about their preferred travel destinations, cycling habits, motives and deterrents. The original design of the grounded theory research was presented as an easy to complete questionnaire that would take a short amount of time, as I was unsure of the participation rate. While I had initially hoped the research would garner 20-30 participants, the 424 female responses to the questionnaire pointed to a high level of interest in this research subject.

Information about the research was shared through flyers posted along central cycling routes across the city. These cycling routes included physically separated from traffic, established routes along residential areas, and a mixture of physically separated and slower traffic zones. The research flyers were directly marketed to women cyclists by posing the question, “Are you a woman living in Vancouver and an avid cyclist or casual cyclist?”. The description of the purpose of the exploratory research was provided directly on the flyers and expressed the importance of gaining female perspectives on the gender differences in cycling in Vancouver. A total of 35 flyers were posted around six different neighbourhoods across the city, allowing diverse participants from various socio-economic demographics. Unfortunately, the flyer was frequently removed at some busy cycling routes across different neighbourhoods . There are some speculations as to why the flyers were removed, but responders did share they often saw male cyclists tearing them down. This behaviour was surprising and contributed to the theory of gender imbalances in cycling due to women feeling intimidated and threatened. Questions were posed through an online survey site, and the link to the site was shared with responders who emailed "Vancouverwomencyclists@gmail.com" and expressed interest in participating. While a QR code could have been included in the posted flyers to allow responders to directly connect to the survey, email correspondence allowed more information and stories to be shared. Most of the participants emailed me with comments thanking me for taking on this research as there is far too little information about women and cycling in Vancouver. According to the online survey site, the meantime for completion of the questionnaire was 6 minutes.

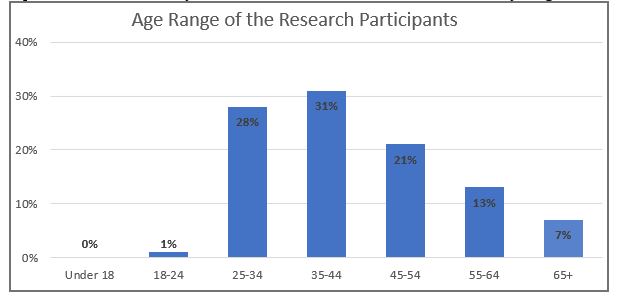

As the flyer was posted in public spaces, it is unknown how many women in total saw the research information. However, 424 women responded to the questionnaire. Most of the responders were between the ages of 35-44, and a close second was between 25-34. Only two responders were under the age of 25. This low rate was surprising as I had anticipated that many participants would be younger women stating that their reasons for cycling were to reduce their carbon footprint and to save money. Economic and environmental reasons for cycling were relatively low compared to other stated reasons: the sense of empowerment, freedom, mindfulness, contributions to mental wellness and connection to their community. While many responders did state practical reasons for cycling, the high number of women who alluded to an emotional connection to cycling was unexpected.

As per the ethical guidelines for social science research with Athabasca University, the research obtained informed consent from those participating in the study (Athabasca University, 2019). As stated in the ROMEO Athabasca Research Portal, informed consent was implied by the overt action of completing the questionnaire. Research participants were emailed the link to the questionnaire, and a copy of the online consent form was included for their records. Comprehensive information about the study was repeated, and it was made clear that participation was voluntary, and they could withdraw at any time. All participants provided their consent once again by emailing and acknowledging their completion of the questionnaire. None of the responders informed me of any concerns they had regarding the research or wanting to withdraw their information.

I used the qualitative online survey method consisting of both open-ended questions and multiple-choice selections with open-ended comments. The open-ended comments and the connection to research participants via email correspondence encouraged participants to share their own cycling experiences. The shared stories, frustrations and anecdotes helped to gain a better understanding of cycling behaviour and barriers. Multiple-choice selections were included to investigate some of the barriers to cycling that other research had reported. While Vancouver boasts a robust cycling infrastructure network, I wanted to consider some of the previously identified factors that might play a role in limiting women's cycling behaviour.

The data collection goal was to obtain valid generalizations on women's cycling behaviours (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). While the data collection period was limited due to time constraints, a one-month time period from September to October of 2019 allowed responders from across the city to observe the flyers and information about the research to be shared via email and Facebook. HUB Cycling Advocacy group posted notification on the research to their September newsletter. MEC allowed for posting on their community boards, UBC shared the research across their staff, and the City of Vancouver shared it across their networks. Overall, the goal was to obtain 20-30 responses from across the city. However, given the current interest in women and cycling in Vancouver, 424 women responded to the survey. The map depicts the responders' wide geographic area, based on the first three digits of their postal code, and the cycling routes where the flyers were posted. I can confidently say that the data analysis constitutes grounds for a valid generalization of cycling behaviours and barriers.

Figure 1 Map depicting location of flyers and survey responders based on the first three digits of their postal code (Maps Vancouver, 2020)

Data collection, coding, memo writing, and analysis were all done simultaneously using the constant comparative method with considerations for feminist constructs (Wuest, 1995). Constant comparative methods helped identify core words, ideas, relationships and themes (Glaser & Strauss, 2017; Lewis-Pierre et al., 2017). The questionnaire responses came at varying intervals, and categorization and comparisons began immediately. As participants provided open-ended comments to six of the eight questions posed, responses were examined multiple times to ensure proper coding. The constant comparative process requires close attention to detail, continuous re-analysis, and understanding of the responses' underlying intent. With each question, the responder would reveal more information about their motives and deterrents for cycling, and how these factors affected one another. The most significant challenge with analyzing qualitative data is the subjective nature of the responses. Grounded theory research methods can reduce subjectivity as theories develop after analyzing the data (Glaser & Strauss, 2017).

The exploration of ideas through personal experiences, direct observations and spontaneous analysis provided the inductive generation of a potential theory based on descriptive concepts (Stebbins, 2001). The 424 research participants, through their stories, experiences, and comments, provided direct representation and strong generalizations of a woman's experiences cycling in the City of Vancouver (Stebbins, 2001).

Identifying keywords, phrases and themes across the responders took dynamic analysis as the participants provided a vast amount of detailed and descriptive data. The initial open coding was conducted by comparing data segments and posing questions such as 'What are the similar factors in the data? How do the participants describe both cycling motives and deterrents? What is the pattern in cycling destinations? Where do women feel inhibited to cycle, and why? (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). This step involved naming words, lines and segments of data (Gallicano, 2013 ). Identifying relationships and connections helped develop patterns, and the process of axial coding further organized the data (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). The third step of coding, known as selective coding, involved re-examining which core variables related to one another and included all the data. This process contributes to building hypotheses and theories of women and cycling in Vancouver (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). Open, axial, selective coding and constant comparative methods allowed various themes to emerge (Lewis-Pierre et al., 2017). The emerging themes were then re-assessed using gender-based analysis considering how men and women use community spaces. For example, safety concerns are an ongoing theme. However, men and women may perceive physical and psychological/emotional safety differently, and the coding and emerging themes needed to reflect this (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). Colour-coding various words or phrases repeated throughout the responses helped highlight themes in the stories and experiences. These ongoing themes contributed to building the theory that perceptions of psychosocial and emotional safety contribute to increased cycling behaviour amongst women.

Exploratory research and qualitative data analysis can be somewhat problematic in that it can potentially be highly subjective. As the lone researcher, I needed to ensure that any emergent generalizations or personal bias did not shape how I assessed and coded the data. I turned to the question of validity in exploratory research, as McCall and Simmons presented in 1969 (Stebbins, 2001). I referenced three identified problems in the validity of exploratory research to ensure that I was not making similar errors:

Responses to the survey questions reflected various motives and deterrents for cycling behaviours (Glaser and Strauss, 2017). Some of the responses were unexpected and described situations I had not considered when I had initially conceived of this study. Qualitative surveys will often introduce unforeseen elements to the research; this is one of the most substantial benefits to using grounded research methodologies (Hanson, 2010).

As a female cyclist; I needed to consider both researcher and participant bias (Stebbins, 2001). How I experience cycling in the City of Vancouver may be very different from another woman's experience. I consider myself to be a confident cyclist that utilizes this mode of transportation as much as possible. However, I do not feel comfortable riding in the rain or cycling to areas outside of Vancouver for safety reasons. My own interpretation of safety was one of physical safety and concern about vehicle traffic. I had not considered experiences of intimidation and threats that other female cyclists had encountered. Grounded theory methodologies can help to uncover cycling factors that may not have been considered and reduce potential bias in the data (Stebbins, 2001). Continually analyzing, coding, and working to understanding what the data was revealing lead to identifying core themes of cycling motives and deterrents for women in Vancouver (Glaser & Strauss, 2017; Woods, 1999).

Table 2 Various motivators for cycling identified by participants. Most participants identified more than one motivator in their open response to Question #3: What are the reasons why you choose to bike? While participants described a significant variety of motives and reasons for cycling, the five reasons identified in the graph were most often mentioned

Based on the high rates of keywords and phrases, the identified motives of cycling for women are categorized as follows.

While many of the research questions provided an opportunity for the participants to convey their motives for cycling, Question Three, "What are the reasons why you choose to bike?" provided open-ended responses that contributed to diverse and unexpected motives. It was not surprising that exercise, environment, cost savings, and worry-free parking were common criteria. The surprising aspect was the number of keywords and phrases pertaining to a strong emotional connection to cycling:

Table 3 Various deterrents for cycling identified by participants. Most participants identified more than one deterrent in Question #6, What are the factors that keep you from cycling more often? Participants were provided with the set choices as identified by previous research on gender and cycling behaviour. The option “other” and opportunity to identify a different factor provided other issues that had an impact on the participants level of cycling.

Table 4 Identifying the “other” factors that impacted how often participants rode their bikes. These reasons may have gender-based implications due to household obligations including child responsibilities. Many also expressed significant concern over theft of a bike due to financial challenges and not being able to afford another one. Gender-based fears of bike thefts have been addressed in a 2015 study from Montreal, “Who cycles more? Determining cycling frequency through a segmentation approach in Montreal Canada”

From the questionnaire participants identified a significant number of factors that affected how much they rode their bikes. Based on keywords and phrases, the most prominent deterrents or cycling barriers for women are as follows:

Most of the participants rated safety as a top priority, and several factors contributed to their perceptions of a safe cycling route. Concerns about weather and riding in the rain was a significant barrier for cycling. Responders spoke of their worries about drivers not seeing them or expecting them to be on the road. However, riding in the rain could also be

"I have had an increase in drivers, all older male drivers, drive aggressively, threaten me, and yell while I'm cycling. This is a huge deterrent."

"Not enough separated bike paths. Stops me from cycling to more places with my kids."

included in a few other core variables based on participants' statements. While reviewing the responses, I did find some differences in perceptions of physical safety and psychological/emotional safety. Separated bike lanes had been mentioned many times, but driver training to improve cycling awareness was also a popular response. Most research on gender and cycling has identified that physical safety is predominantly more of a concern for women than men. While several responders reported aggressive driving and vehicles coming too close to cyclists, some also reported dangerous behaviour from male cyclists (such as: passing on the right, cutting them off, cycling too fast and flying through stop signs). Some of the responders mentioned that male cyclists behaved too competitively on the bike routes and often wanted to aggressively pass female cyclists.

Fear of bike theft was a concern and an identified barrier by more than half of the responders. As previous research has shown, both men and women are concerned about bike theft and safe locations to lock their bikes when they reach a destination. This barrier

“Not enough secure bike parking. I get anxious about going somewhere and not knowing if I'll be able to park my bike somewhere close by where it won't get stolen. Vancouver is infamous for its bike theft. I feel confident biking to work partly because there is a secure bike locker in my building”

may not necessarily be gender-based, but it may have some connections with the gender pay gap. Some responders had identified that they wanted to purchase an e-bike to cycle to more

"No SECURE place to leave my bike when I do errands or go to evening classes”

destinations, but they were too concerned about theft. Responders also mentioned that they would like to see more secure bike parking in central locations, especially in the Downtown core.

Most of the responders had stated that they wanted to cycle more often, but household errands were too challenging to complete by bike. There was mention of timing issues around leaving work and picking up children from school or daycare and carrying heavy or bulky groceries. Household errands are also tied into the topography and trying to navigate hills. Trying to carry heavy groceries while cycling up a steep hill proved very challenging

“Have a child - makes more difficult to pull/park trailer, and roads not safe enough for child to travel on own.”

“Kids are heavy and don't like getting wet. Child trailers are expensive to get good ones.”

“-lack of secured places to park bike - can't carry enough on bike when doing a large grocery shopping run and don't want to get a trailer; also want to keep frozen/perishable groceries out of the sun in the summer-need to transport elderly parent”

for many responders. Some of the responders that were able to complete a wide range of household errands mentioned using an e-bike or e-cargo bike, while others said they wish they could afford an e-bike.

Many research participants reported that cost savings were a factor in choosing to cycle. The expenses of bicycles and cycling accessories could be a barrier for them to cycle more often. Economic concerns are one of the factors that affect weather-related barriers. Some responders had shared that good raingear was too expensive, and it regularly needed to be replaced. Other participants stated that they wish they could afford an e-bike or e-cargo bike to help them complete household errands, navigate hills, and complete a trip more efficiently. Electric-assist bikes can range from $2,000 - $9,000, making them cost-prohibitive to many cyclists who are seeking a more affordable way to travel (Epic Cycles, 2018). Responders who identified that they had an e-bike or e-cargo bike were more likely to participate in a wider variety of cycling destinations and complete far more household errands. These responders tended to be within the age range of 35-44, and perhaps of a higher household income level. Improving access to e-bikes and e-cargo bikes may positively impact the rate of female cyclists, as it would address varying and diverse needs. These electric-assist bicycles can overcome barriers such as topography, completing various household errands and arriving at destinations, "not looking like a hot mess" (Cyclist, 2019).

“I think neat bike options for women to carry kids is key and we need more of these options imported in and made more financially accessible!”

Approximately 30% of responders had mentioned having a challenging time cycling to different destinations due to perceptions of femininity, beauty and professionalism. These responders had concerns about being sweaty, messy or dirty clothing, smeared makeup, helmet hair, or appearing unprofessional at work. These factors would most certainly be gender-based as most men do not have the same pressures as women do to live up to an unrealistic standard of beauty. E-bikes were often mentioned as a solution to arriving at a destination looking more put-together and professional. While concerns about messed-up hairstyles or wrinkled clothing may seem irrelevant, some researchers have found that there can be a gendered bias in workplace appearance (Lee, 2016). This bias may hinder women who want to cycle to work but feel inhibited due to the social and gendered expectations of appearance (Lee, 2016).

“E-bikes are the future of cycling, in my opinion. I no longer arrive at work with sweat running down my face, can change directly into my uniform without showering, and I am able to load up my bike with heavy groceries after I finish my commute”

“I am a single mom running a home Daycare, so I can’t transport kids via bike, so I use a van. Carrying a kid takes up bike space and weight, so errands with him is hard. I’d like a cargo style bike, or electric assist, but cost is prohibitive.”

“I wish I could afford an electric bike!!!”

A surprising number of responders mentioned feeling afraid or intimidated by aggressive behaviours from male drivers and cyclists; these include being yelled at, sworn at, male cyclists making inappropriate comments, and behaving too competitively. Approximately 16% of the responders stated they felt threatened, intimidated, or afraid while cycling, which significantly affected their overall cycling rates. Some of the responders had mentioned that their male friends or husbands did not experience the same level of aggression directed towards them while they were cycling. Others felt this level of hostility directed at female cyclists was misogyny that no one wanted to speak about. The stories and experiences that the women shared of being harassed while cycling is shocking and untenable. While there may be several impediments to cycling, such as Vancouver's topography, the amount of rain,

“There are so many more things a woman needs to freshen up I find it challenging to have the change of clothes, toiletries, extra pair of shoes to all get in my backpack when I cycle.”

“I want to elaborate more on the dress code option. I think what held me back for a long time is a 'personal dress code' and not wanting to show up to work sweaty and have to change/shower/do hair or makeup. I've been able to work around that and still maintain my personal standards for appearance, but I recognize my standards are impacted by societal pressures, norms and stereotypes imposed upon women.”

“I have been told once by a colleague/person in somewhat of a position of authority that my appearance was unprofessional. I was wearing business casual clothes, so I can only assume it was because I was wet. Fat chance a man would have received that comment.”

and concerns over bike theft, steps must be taken to mitigate the levels of intimidation and threats that women cyclists have experienced. Cycling infrastructure does not often consider the differences in how women and men may use community spaces. If research finds that separated cycling lanes improve cycling behaviours, there is rarely a further investigation into the differences in how men and women perceive safety. While this study looked at the emotional and psychosocial aspects of safety shared by women, further research may want to consider men's unique perspectives on motives and deterrents of cycling. By directly asking male cyclists about their interactions with other cyclists perhaps there will be some insight gained into why so many women expressed feeling threatened and intimidated while cycling. If a significant amount of male’s cycle for exercise and an efficient way to travel to a destination, perhaps recreational cyclists who may travel at a slower rate are looked upon as obstacles rather than just another cyclist. Encompassing different perceptions and considering gendered experiences may shape how municipalities market the idea of inclusive cycling along various cycling routes. Campaigns reminding everyone that cyclists encompass a significant breadth of people, and to show courtesy and respect along the routes could help counter potential bullying and intimidation.

“Specifically related to women and cycling: I have been subjected to harassment from male drivers, on numerous occasions and in ways that I feel certain would not have happened if I was a man”

“Feeling unsafe even in bike lanes or unwanted is the biggest factor in discouraging me from cycling”

“Aggressive behaviour from male cyclists. Aggressive behaviour from drivers (yelling, horn blowing, getting too close intentionally)”

“I sometimes get abuse when I cycle. I think it is because I am a woman, I am not a thin person, I don't wear special gear when I cycle. Both cyclists and drivers (male) sometimes yell at me. Things like "get real shoes", "stupid", "fat B**ch." It is really awful and always ruins my ride. Just run of the mill misogyny/fat phobia but we need to acknowledge we still have a long way to come. I doubt that men face the same abuse on the streets. My friend actually saw a man angrily ripping down your posters. That is why I participated.”

“Male cyclists and male drivers can be quite intimidating. Male cyclists don’t take it well when you pass them and then they do everything they can to pass you back and put you in your place”

“Many cyclists, mostly male, are cycling quite dangerously - running stop signs and red lights, cutting off cars and pedestrians. I am very happy that more people are cycling, especially women - but I wish we cyclists could be more courteous to each other, and not give each other a bad name."

“I sometimes feel that men are more readily aggressive to female cyclists. I have had a few encounters of male drivers being rude and aggressive, without provocation on my part. My husband, who cycles regularly, has suggested that it might be a male / female thing as he doesn't feel men react to him in the same way.”

“I think cycling in the downtown Vancouver core is not really welcoming for women: I bike during the week and I notice it is quite driven by men who are fully equipped with bike gear, are fast and can be very vocal. I think it can be intimidating for some.”

“Lately, I've been put-off from cycling because of how I or my friends have been treated by drivers (e.g., bullying, impatience, aggressiveness, or obliviousness) and to a lesser degree by other cyclists. I've been yelled at from across multiple lanes of traffic to get to a bike route; sworn at by drivers; honked at for taking the middle of a lane (where I felt most safe); corralled into a curb/onto a sidewalk by someone using their truck to intimidate me off the road… All this bad behaviour has soured my mood towards cycling such that it is not enjoyable most of the time.”

This research describes the perceptions, experiences, and barriers that many female cyclists in Vancouver encounter. Many of the survey respondents expressed wanting to bike to as many destinations as much as possible. Unfortunately, barriers such as gender-based influences on mobility, concerns over safety (physical and psychological), and perceptions of appearance may hinder cycling behaviours. It is essential to mention that not all survey participants were deterred from cycling; approximately 8% stated they cycled as much as they wanted without barriers and 10% were unsure about potential barriers. Their confidence in cycling may be due to various factors such as length of time cycling, social supports from family, friends or co-workers, or ability to navigate cycling routes. However, it is crucial to recognize that 82% of responders experienced some barriers to cycling. While cycling infrastructure contributes to perceptions of personal safety and accessibility, there are still factors that leave many women feeling vulnerable, threatened and discouraged from cycling. These factors often come from aggressive behaviours from drivers and other cyclists, predominantly identified as males. Feeling emotionally unsafe and vulnerable are deterrents that many other cycling studies have not considered. One of the benefits of a grounded theory study is understanding the perceptions of cyclists' different experiences. A significant number of responders expressed their emotional connections to cycling using phrases such as, "I feel free," "I feel empowered," and "Contributes to mental health." In this qualitative-based study, the motives and deterrents for cycling show significant gender-based differences in relationships and experiences with cycling.

There are some actions that the City of Vancouver could take to improve a woman's sense of safety while cycling, and potentially contribute to more gender-balanced cycling routes.

Many responders shared that they felt frustrated, trying to navigate cycling routes, which diminished their confidence in cycling. A five-km radius map could help cyclists navigate shopping areas, safe bike routes, and commercial districts. Providing cyclists with easily accessible route planning can maximize their travel efficiency and help them to accomplish household errands by bike

Vancouver offers an expansive network of bike-share programs located in diverse areas across the city. If the city also provided e-bikes and e-cargo bikes as part of this bike share, it could help many cyclists complete more cumbersome household errands such as grocery shopping or carrying bulky items.

Reducing threatening behaviours from cyclists and drivers will be a significant challenge, and something the city will need to address. Altering attitudes, behaviours, and aggressive language will need ongoing forms of communication and social supports through the development of cycling discussion groups, marketing diversity in cycling, driver education, and social rides to empower inexperienced cyclists.

“- separated bike lanes are the only safe way for cyclists to travel and more must be built incl. on useful paths to meaningful/practical destinations - cyclists and pedestrians should be given equal priority (for comfort, convenience, safety) to drivers of motorized vehicles in ALL decisions regarding transit - getting and keeping a driver's license must include instruction and laws about respecting the safety of cyclists - much tougher penalties for drivers who hit and/or kill cyclists - businesses and offices to provide change rooms and secure bike storage facilities for cyclists so commuting is a viable option - consultation with cyclist organizations before implementing any infrastructure so that money and time (and patience by all users) is not squandered - cyclists pay municipal taxes so our right to cycle safely and conveniently must be equal to that of drivers”

While analyzing the research findings of women and cycling in Vancouver, it is also essential to consider the design of urban areas and the differences in how men and women use public spaces. While this subject is vast and should be pursued in a future research project, many participants in the study expressed their lived experiences of not feeling safe in their city. Fear, intimidation, and perceived threats shaped how they used their urban environments, which affected how often they biked in the City (Day, 2011). Some participants shared that they bike because they do not feel safe taking transit or walking alone in the evening. A particularly aggressive act that occurred during this research study was when the flyers were torn down along various locations. A few of the research participants said that they had witnessed some men looking for the flyers along the cycling routes and tearing them all down. I am curious why these men felt the need to do this action and why they felt so angry about the survey. Perhaps, this is yet another type of research that should be conducted, having an open dialogue about how men and women use public spaces and how we can create more inclusive communities.

“It’d be nice to have more female focused rides that weren’t all about going fast and racing. The issue with female cyclists who want to get into riding is that they’re too concerned that they aren’t fast or won’t be able to keep up with other people. We need to try and break this norm and let people know that they can cycle for fun.”

The City of Vancouver prides itself on creating equitable and inclusive public spaces (City of Vancouver, 2020). However, recognizing the differences in how women experience and use these spaces could vastly improve safety and equitable access to public areas (Foran, 2013). Engaging women's perspectives in the design and improvement of cycling infrastructure may help create gender-balanced cycling behaviour (Foran, 2013).

To understand the prevalent gender gap in cycling within the city of Vancouver, it is essential to consider personal experiences, cycling preferences, and the motives and deterrents that influence a women’s decision to ride a bike. While the city has the protected cycling infrastructure identified as a feature for increasing the rates of female cyclists, other factors and initiatives must be considered in order to create gender balanced cycling behaviours. Analysis of the motivators and deterrents for women cyclists can improve our understanding of the gendered uses of community spaces such as cycling routes and pathways.

While previous research on gender and cycling often focused on physical safety and separated bike lanes, this research addresses women’s perceptions of psychological and emotional safety and how this impacts cycling behaviours (Damant-Sirois & El-Geneidy, 2015; Le et al., 2019; Mertens et al., 2016; Teschke et al., 2017; Winters & Cooper, 2008; Winters et al., 2011). To improve the rates of women cyclists, it takes more than just separated bike lanes and pathways. Active transportation initiatives must consider a variety of factors that influence and shape a woman’s decision to ride a bicycle, including the gender differences in the use of community spaces (Day, 2011; Foran, 2013). Interest in the research subject of women and cycling in Vancouver was far more popular than I had originally expected. Responses to the survey were passionate and filled with stories and scenarios of the joy, mental wellness and community connections that cycling contributes to their life. Unfortunately, too many women shared experiences of feeling intimidated and threatened while trying to cycle. Gendered experiences in cycling must be acknowledged and valued if the city of Vancouver and other municipalities strive to achieve inclusive, gender-balanced cycling rates. During a conversation with a member of Vancouver’s Transportation Planning Department, the staff member admitted that the city has not identified the demographics of who is using the cycling routes, and therefore, Vancouver does not have a clear understanding of the barriers that women may face while cycling (Douglas, 2019). The Transportation Planning Department does acknowledge that there is a gender discrepancy in cycling rates, but they are unsure of how to contribute to gender-balanced cycling routes (Douglas, 2019). According to the 2016 BC Climate Action Toolkit, 39% of cyclists using a well-established, centrally-located , separated bike lane were women (BC Climate Action Toolkit, 2016). If the rate of women cyclists in Vancouver increased by just 11%, the rate would be at par with male cyclists. This research study has described how 16% of women responding to the survey felt intimidated and threatened while cycling and as a result, reduced their cycling behaviours. Implementing the recommended actions such as creating wayfinding maps to improve route planning, offering diverse bicycles within the city run bike-share program, and developing marketing campaigns to highlight and educate on the diversity of cyclists, could potentially lead to a significant increase in gender balanced cycling rates. These actions could also easily be implemented within other cities and regions to increase the rates of women cyclists. Further research examining the gendered experiences in cycling routes and separated bike paths in Vancouver and other cities could improve understanding of how women perceive these community spaces and how men interact with other cyclists. This research paper did not examine the views of male cyclists, but further research should consider gendered perceptions of public spaces such as separated cycling routes. Additional cycling research should also consider how ethnicity, cultural and socio-economic differences factor into cycling behaviours. To create true diversity and inclusion across active transportation initiatives, cities must acknowledge how varying demographics use community spaces and implement plans to embrace these differences.