Jessi Adams-Crawford was born and raised on the traditional unceded lands of the Gidimt’en Clan and the Wetsuwet’en people within the northern interior of British Columbia. In 2001, she moved to Lethbridge, Alberta and has since settled on the traditional lands of Siksikaitsitapi, the Blackfoot Confederacy, and the Treaty Seven region. Adams-Crawford is passionate about Indigenous sovereignty and social justice issues due to her close relationships with Indigenous individuals and her experience growing up along the infamous Highway of Tears. She began her BA/BEd degree at Athabasca University in 2020 and has since transferred to the University of Lethbridge to attend the Education program. Her humanities major focuses on English, Indigenous Studies, and history. The inspiration for the manuscript is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action and the need for immediate policy changes. The research for this manuscript prioritized Indigenous perspective and sources where available because Adams-Crawford understands the importance of Indigenous perspective regarding Indigenous social issues.

Lethbridge is in urgent need of Indigenous-led urban land-based healing programs. This smaller southern Alberta city was recently home to one of the busiest safe consumption sites in all of Canada and has rates of opioid overdoses and deaths that far exceed the national average. Intertwined with fatal substance misuse rates is an overrepresentation of Indigenous people experiencing homelessness in Lethbridge. The suffering inflicted by the residential school system, racism, and the continuous removal of Indigenous children has produced trauma for many Niitsitapi’. Generations of Blackfoot families have felt the harmful effects of the separation, addictions, and violence initiated in their communities through residential school exposure, racism, and the continuous removal of their children. Mainstream society must view Indigenous knowledge as an equitable source of scientific information, and Elders deserve respect and opportunity to use the Niitsitapi’ ways of knowing to implement programs to heal the people of the Blackfoot confederacy. Through the development of Indigenous identity, reconnection with land, and the creation of valuable relationships, there is potential for long-term healing for those experiencing substance misuse, homelessness, or both. Urban land-based healing camps provide these outcomes through Indigenous teachings, building self-esteem, and reintroducing cultural experiences in their programs.

Keywords: Indigenous knowledge, substance misuse, homelessness, Lethbridge, urban land-based healing

Lethbridge, Alberta, located in the heart of the Blackfoot confederacy’s ancestral lands, is witnessing a flourishing revival of Indigenous culture after a genocide. Historical colonial policies of the Indian Act of 1868 failed to eliminate Blackfoot culture; however, they traumatized and fractured the Indigenous way of life by oppressing their religion, language, critical relationships, and identity. The implementation of residential schools, the sixties scoop, and the foster care system severed the transfer of traditional knowledge by removing children from their families and communities during critical periods of learning and development (Coyhis, n.d.). In addition to this social disconnect, the relocation and removal of Indigenous people from their traditional lands–sacred places and region-based resources–created a spiritual disconnect or spiritual homelessness, for their spirituality is embedded in connection with the land (Bastien, 2004; Victor et al., 2019). Indigenous people have suffered significant loss, pain, and oppression, creating “soul wounds,” defined as “trauma that is multigenerational and cumulative over time; it extends beyond the life span,” commonly known as intergenerational trauma (Coyhis, n.d.; Weasel Head, 2011). An adverse outcome of these soul wounds is an overrepresented population of Indigenous people in Lethbridge managing substance misuse, homelessness, or both.

While the focus remains on the adverse outcomes of the trauma endured by Indigenous children, one must acknowledge the resiliency of the Niitsitapi’ and not aim to generalize Indigenous people, nor assume substance misuse and homelessness are limited to them. The goal is to acknowledge the harm of colonial policies, the continuation of reactive practices instead of preventative approaches, and the responsibility of all Treaty Seven people to create change. Through an analysis of historical events, current social issues, Eurocentric methods of support, and Indigenous-led healing methods, one can identify the importance of cultural identity, interconnectedness, and Indigenous-led initiatives in healing trauma. Lethbridge urgently requires a culturally based intervention, and Canadians have a moral and fiscal responsibility to support Indigenous land-based urban healing programs. Leaders and policymakers must go beyond indigenizing current institutional centres and embrace Indigenous Elders’ scientific knowledge and leadership while providing the additional resources they may require to heal those dealing with substance misuse and provide adequate housing for those experiencing homelessness (Redvers et al., 2021).

The Blackfoot Confederacy is comprised of many unique Blackfoot-speaking nations. The Kainai (Blood), Siksika (Blackfoot), Piikani (Peigan), and Amskapi Piikuni (Blackfeet) refer to themselves as Niitsitapi’, which translates to ‘the real people,’ or Siksikaitsitapi meaning ‘Blackfoot-speaking real people’ (Alberta Teachers Association, 2018; Bastien, 2004). For clarity of language, the use of the terms Niitsitapi’ or Indigenous will apply to Blackfoot people in proximity to Lethbridge, whereas the term Indian will only be used for historically accurate names. In the southern region of Treaty Seven territory, east of the Kainai and Piikani reserves, lies the city of Lethbridge, with a modest population of 98,406 (Statistics Canada, 2022; Alberta Teachers Association, 2017). The Blackfoot nations comprise the majority urban Indigenous population, accounting for 5.8% of the total city population (Victor et al., 2019). Although other Indigenous groups have come to call Lethbridge home, the focus will remain on the groups whose ancestors lived on these lands for thousands of years.

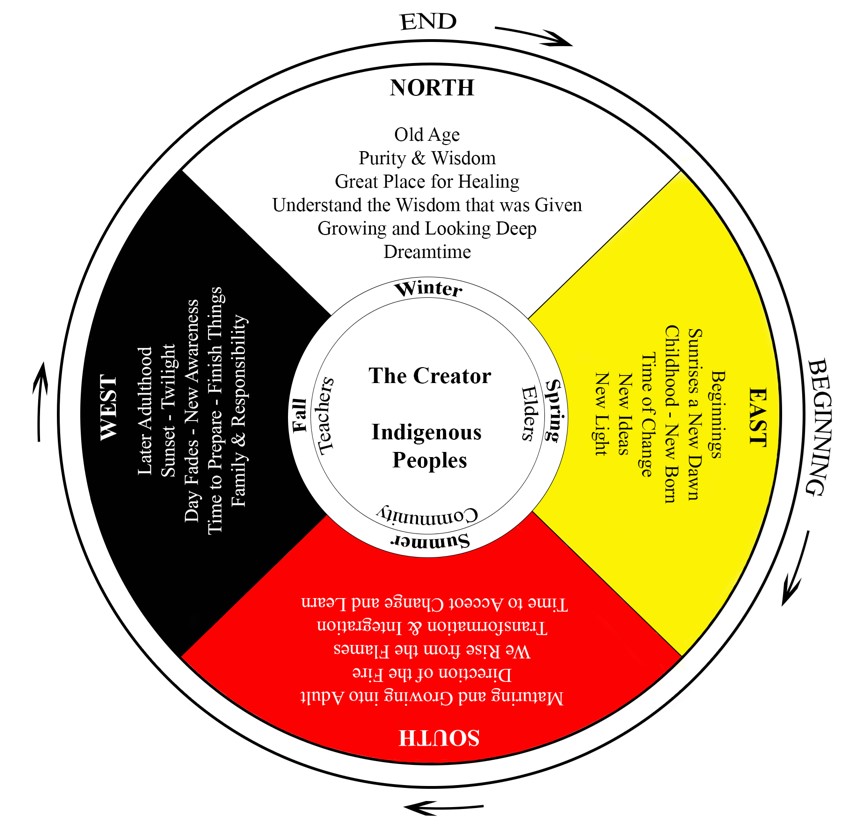

Throughout history, the Niitsitapi’ have flourished living off the lands of the Alberta plains; they have a valuable knowledge system that is scientific, holistic, and deeply spiritual, as it is rooted within the relationships between all living things. Dr. Betty Bastien (2004) of the Piikani nation states in her book that the universe has a sacred power and influence that works together in reciprocity with all interdependent parts. The natural world intertwines with the spiritual world. This experience-based knowledge is orally transmitted through intricate kinship relations and passes from parents, grandparents, and elders to children. Although oral transference of Indigenous knowledge is dominant, many groups have a medicine wheel visually representing their belief and knowledge system. Dr. Richard Katz (2017), a long-time clinical psychology professor who focuses his research on the respectful exchange between Indigenous health teachings and western psychology, explains Indigenous knowledge systems as:

A set of teachings that become active as one engages in them, working them into one's life to better understand them. The medicine wheel is typically conceived of as a circle consisting of four equally valued sections, each of which expresses many layers of meaning. The sacred number four is expressed in a variety of interconnected, equally important realms and experiences, such as the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. The four seasons and four directions also offer guidance about the tasks of living in the four stages of life: infancy, adolescence, adulthood, and old age. The Creator is seen as the center of the Medicine Wheel, animating the entire process.

The medicine wheel’s teachings create a circular path of knowledge and growth, unlike the Eurocentric linear model, allowing for issues in life that may appear at differing times to be re-examined and resolved (Katz, 2017); this foundational learning relieves pressure to succeed when one is not ready, and can remove feelings of shame or failure. All aspects of Niitsitapi’ ways of knowing are sacred knowledge which Blackfoot children must learn to help them find their place in the universe. Experiencing connections with the natural world is essential in the integration of the ways of their ancestors, a process based on developing Indigenous identity through knowing and living the Niitsitapi’ traditions (Bastien, 2004). During the nineteenth century, colonial policies were implemented to disrupt the development of Indigenous identity; the government condemned the “heathen” ways of the Niitsitapi’ and initiated many political structures which embodied the systemic racism still evident today (Bastien, 2004). Assimilation of Indigenous people to Christian cultural ideologies became essential, so officials began removing children to end the spread of cultural practices and spirituality to “knock [them] out of balance” (Coyhis, n.d.; Bastien, 2004).

With the introduction of residential schools, there was a disruption in the cultural transmission of knowledge, and the valued interdependence of the culture was lost to the dominant culture’s independent ideologies, forcing assimilation (Bastien, 2004). The Indian Act, amended in 1894, empowered Indian agents to forcibly remove children and relocate them to these schools to be kept, cared for, and receive a western education until they were eighteen (Government of Canada Publications, 1978). Within an 85 km radius of Lethbridge were four residential schools, three located close to the Kainai reserve. St. Paul’s and St. Mary’s Indian residential schools were in Cardston, and The Immaculate Conception Boarding school was in Stand Off. The Peigan Indian Residential school was in Brocket, Alberta, on the Piikani reserve (CBC News, n.d.). Under the authority of the Roman Catholic church and the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, countless Indigenous children attended these schools from approximately 1884 until 1975 (CBC News, n.d.; Smith Sweetgrass, 2015).

Throughout the years in school, the implementation of oppressive practices, such as hair cutting, foreign clothing, forbidding native languages, and conversion to Christianity, facilitated the assimilation of these children (Belanger, 2018). Beyond these standardized practices, many children experienced neglect, malnourishment, illness, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse (Nutton & Fast, 2015; Smith Sweetgrass, 2015). Surveys indicate that 48%–70% of residential school survivors, who were willing to report their experiences, were victims of physical and sexual abuse; the actual number of maltreated children is likely much higher due to unreported incidents and childhood deaths occurring within the school (Nutton & Fast, 2015). These children also endured unfamiliar and severe punishments for non-compliance. The foreign forms of discipline included humiliation, shame, submission to authority, and regimented behaviour. Some residential school survivors who became parents continued this learned form of punishment with their children (Nutton & Fast, 2015; Weasel Head, 2011). An Indigenous lecturer, Don Coyhis (n.d.), shares that before children attended residential schools, Indigenous people did not know about domestic violence, sexual abuse, and physical abuse. Due to the disruption in cultural parenting education, Indigenous children became Indigenous adults missing cultural knowledge meant to foster positive parenting roles (Coyhis, n.d.). The government's goal to raise children outside the influence of their parents, extended families, and culture has created generations of parents simultaneously managing trauma and raising children. Some of these parents resort to the abuse and neglect they experienced, subsequently initiating the removal of their children by government officials, which continues to sever cultural ties for many generations (Belanger, 2018; Nutton & Fast, 2015; Weasel Head, 2011).

The federal government did not respond to reports of abuse during the operations of residential schools. Ironically, the cycle of abuse carried forward from those schools has led to an intervention by government agencies to remove Indigenous children and place them with non-Indigenous caregivers (Alberta Children Services, 2022; Nutton & Fast, 2015). Mass removals began with the sixties scoop, where, during the 1960s to 1990s, government servants removed countless children from their families. The racialized ideology that non-Indigenous families were considered superior caregivers guided the removal of Indigenous children who were placed in foster care or adopted by non-Indigenous families. An estimated 20,000 children were adopted without the consent of their families or tribes (Belanger et al., 2013). The Indian Act negatively influenced the attitudes of non-Indigenous people towards Indigenous cultural practices, creating a ripple effect of racism within current policies that continue to remove Indigenous children (Belanger et al., 2013). Several Lethbridge foster homes are run and operated by non-Indigenous families, and although most caregivers are compassionate, Niitsitapi’ children are placed in culturally unsuitable environments. Slowly, policies are changing the social service system, kinship placements are rising, and foster parents are encouraged to participate in Blackfoot cultural activities with the Niitsitapi’ children in their care (Government of Canada, 2022; Alberta Government, 2017). These policies respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada's (2012) call to action regarding child welfare and the demand to reduce the number of Indigenous children in care and to keep them in culturally enriched environments, no matter where they reside—a welcome policy change that starts the path to reconciliation. However, preventative measures are required to lower the number of Indigenous children in foster care.

The number of Alberta’s Indigenous children in care is rising. In June 2013, a reported 5,625 Indigenous children – 69% of all apprehended children – were in foster care (Alberta Children Services, 2013). Nine years later, 5,729 Indigenous children – accounting for 73% of children – were in foster homes or kinship care. These are distressing statistics in a province where Indigenous children account for only 10% of the total child population ages 0-17 (Alberta Children Services, 2022). Canada has established the need for reconciliation, but current practices appear reactive in nature and do not address the core problems. Officials remove children from harm but ignore the concept that removing children creates future adults dealing with mental illness, trauma, and substance misuse disorders. These individuals may become parents who eventually have their children removed by social services. A preventative approach would be effective at healing the individual, which could lead to a reconnection with their children, parents, and community. Solutions might include childcare immersed in traditional learning experiences, Niitsitapi’ camps, attending the Sundance, or weekly traditional cultural immersion activities, and require foster parents to meet these requirements.

The Kainai and Piikani have Indigenous-managed child and family services available, but urban Niitsitapi’ may not have appropriate access to these services based on geography and socioeconomic restrictions (Government of Canada, 2022). Although government agencies aim to protect children from harm, the removal process blocks the children’s path of reconnection to their Indigenous roots, which extinguishes Indigenous identity and pride. The overrepresentation of Indigenous children in care foretells a future generation of adults without the traditional teachings or sense of cultural identity. These foundations of self are crucial in developing strong self-esteem, which is a protective factor when dealing with substance misuse and racism (Nutton & Fast, 2015). Bastien (2004) emphasizes this point when she explains, “each Niitsitapi’ generation that has survived the genocidal policies has drawn from the strength derived from our ancestors and our connections with the natural alliances.”

An Indigenous man in Lethbridge, Jared, describes his experience growing up in foster care, “I never got the opportunity to learn about my culture. I was sort of against it for a while because of how I was raised.” However, since reconnecting with his cultural identity through Indigenous-managed programs, he states, “it is important… to learn and to pass [cultural knowledge] down, and I think it is another way for us to step towards healing” (Victor et al., 2019). For her master’s thesis, scholar Gabrielle Weasel Head (2011) interviewed a woman raised in a foster home. She recalled a good upbringing and strong bond with her adoptive mother. However, she lacked her Blackfoot identity and the interconnectedness of her culture. She mentions that her adult life contained many addictions, abusive relationships, and poor life choices. Ultimately, she did not have the opportunity to reconnect with cultural ways, and her circumstances caused her to surrender her children to the foster care system (Weasel Head, 2011).

Beyond the systemic racism embedded in society and politics, numerous Indigenous people in Lethbridge report experiencing individualized racism. In a Facebook post, a local Blackfoot woman, Deloria Many Grey Horses (2021), recounts an interaction between herself, a Blackfoot man, and non-Indigenous individuals. This Blackfoot man was trying to get a coffee, but he was afraid the store would make him leave. Many Grey Horses bought him a coffee and sat with him because he “didn't look so good.” He told her of the recent murder of his good friend. While visiting, she overheard a group say, “look at these gross dirty Indians.” Many Grey Horses (2021) pleads with her non-Indigenous friends to hold one another accountable as she reminds everyone, “having people give you dirty looks and say mean things to you on the daily basis isn't only painful, but it's a big part of the problem.” Lethbridge’s racial issue stems from stereotypes applied to all Indigenous people based on the few seen panhandling or under the influence of substances in the downtown core.

Galt Gardens is a developed public park in the center of Lethbridge where many organizations held family events to unite the community (Fominoff, 2018). However, in recent years, this park has become the location for gatherings of people experiencing homelessness, substance misuse, and other illegal activities (SCS Review Committee, 2020; Fominoff, 2019). CTV reporter Sean Marks (2021) interviewed Mark Brave Rock, a Blackfoot leader and founder of Sage Clan, an Indigenous-led support group. Brave Rock shares his concerns in this interview: “it’s time for change at Galt Gardens… it’s an eyesore, and it reflects a lot of what the community thinks of the Blackfoot people, which is not true,” and he believes it is time that the park “goes back to children, goes back to the community. It’s not a place for illegal activity” (Marks, 2021).

The Lethbridge Police Service has initiated a safe walk program to patrol Galt Gardens and downtown Lethbridge, offering safety for citizens frequenting the area (Downtown Lethbridge, 2022). Some have claimed this program is racist, and accusations of racism plague the Lethbridge Police Service. According to CBC journalist Bryan Labby (2017), Indigenous people are five times more likely to be carded than non-Indigenous people. He interviewed Cherilynn Blood of the Kainai nation, who recalls being a passenger in a Caucasian driver’s car, when she was asked for identification, but the driver was not (Labby 2017). Individual racism is not limited to those dealing with substance misuse and homelessness; it is experienced by many Indigenous individuals in Lethbridge, causing unnecessary humiliation and pain. Unfortunately, racist comments and the agony they cause can lead to substance misuse as individuals attempt to self-medicate and bury the pain (Brave Heart, 2003).

Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart (2003), who focuses her research on Lakota historical trauma, describes substance misuse risk factors as trauma exposure, ineffective parental disciplinary practices, absence of family rituals, alcohol-related violence, parental mental health issues, and verbal, physical and sexual abuse. Lethbridge has a disproportionate number of Indigenous people managing substance misuse – especially opioids (Government of Alberta, 2021). In early 2018, within a one-week period, over fifty community members had overdosed. Fatal overdoses in Lethbridge produce a significant death rate of 83.9 per 100,000, compared to the national average of 32.4 per 100,000 (Mahoney, 2018; Dryden, 2021). Considering a population of under 100,000 people, Lethbridge's Indigenous deaths from opioid overdose is 3.5 times higher than Calgary's (Government of Alberta, 2021). ARCHES, a non-profit organization that aims to reduce the harm associated with HIV and Hepatitis C in southwestern Alberta, attempted to lower overdose deaths by opening a Safe Consumption Site (SCS) (ARCHES, 2020). However, the site increased harm to vulnerable individuals, likely due to the perceived sense of safety and accessible naloxone administration should they accidentally overdose (Hanson et al., 2020). A review of the SCS documented a 400% increase in overdose deaths within a 500m radius of the site and a 200% increase within a 2000m radius; the number of clients accessing the site almost doubled in one year, from 64,000 in a six-month period to almost 120,000 the following year for the same time frame (SCS Review Committee, 2020). Many clients were without stable homes, and approximately 70% were Indigenous (Dryden, 2021).

In 2020, the Indigenous death rate was seven times that of non-Indigenous people in Lethbridge. During an investigation of the site, ARCHES could not provide the reviewers with satisfactory referral documentation for treatment services. They provided harm reduction but nothing substantial to aid long-term care or recovery (Dryden, 2021; SCS Review Committee, 2020). These statistics aim to educate, not discriminate against those struggling with substance misuse; Lethbridge’s vulnerable population deserves non-stigmatized equitable physical and mental health opportunities (Winters & Harris, 2019). The Niitsitapi’ should have access and opportunity to engage in meaningful and culturally engaging healing or rehabilitation. Change needs to occur, and soon, for the safe consumption site’s Eurocentric four-pillar method of harm reduction (without the coinciding methods of prevention, enforcement, and treatment) may have expedited increasing trauma in the Niitsitapi' community through the loss of loved ones to overdose, and orphaned children placed in care (SCS Review Committee, 2020; Pijl, 2020).

Substance misuse often coincides with homelessness (Victor et al., 2019; Weasel Head, 2013). Indigenous homelessness is isolation from relationships to land, water, place, family, kin, animals, culture, language, and identity (Thistle, 2017). All these facets are linked to the spiritual aspect of Indigenous ways of life, and a deficiency of such relationships throws individuals out of balance; the absence of cultural connections creates the experience of spiritual homelessness (Victor et al., 2019). Some Elders believe that people are staying in survival mode because they have lost the ability to dream of a better way of life, and dreams are how Indigenous people connect with the spiritual world (Bastien, 2004; Hojjati et al., 2017). Spiritual homelessness often leads to physical homelessness–a lack of structural habitation (Belanger et al., 2013; Victor et al., 2019; Thistle, 2017). This paper will address the most critical form of homelessness: those who are unsheltered or in emergency shelters, those who are seen around the city panhandling, escaping abusive relationships, or just trying to find a safe place to sleep the night (Belanger et al., 2013). The biggest hurdle for policymakers and financial managers within the government is the lack of empirical data. Canadian society utilizes quantitative and qualitative data to make decisions; however, enumeration of individuals experiencing homelessness is scarce (Katz, 2017; Belanger et al., 2013). Officials could come to Lethbridge and visit Galt Gardens, the emergency shelter, Harbour House, and the Civic Centre outdoor fields to witness the vast population of those in need of safe housing but denying the value of anecdotal evidence restricts the implementation of change.

In 2006, 47% of those experiencing homelessness in Lethbridge were Indigenous. Again, in a city where the Niitsitapi’ account for roughly 6% of the total population, this data indicates the substantial proportion of Indigenous people experiencing homelessness (Belanger et al., 2013). If there were to be a census, one might predict these numbers are on the low end of the scale compared to the current situation in Lethbridge; this speculation is based on the rapid growth of the SCS alone and the clientele seeking their services. Indigenous individuals’ obstacles to securing safe housing often include landlord racism, low income, incarceration, substance misuse, lack of family support, and the desire for social connection (Belanger et al., 2013; Weasel Head, 2011). Those who find housing sometimes choose to return to shelter life to reconnect with their shelter community, looking for their missing relationship–their family (Weasel Head, 2011).

In Lethbridge, the emergence of encampments represents the desire for family and community, and instead of expediting the creation of safe housing to eliminate the need for encampments, the city’s response is to dismantle structures and send away those with no place to go (Goulet, 2022; Marczuk, 2022). Mike Fox, director of community services for the city of Lethbridge, states in an interview, “[we] need to focus efforts, [on] how best to advocate to the provincial government for permanent housing solutions for those residents who are experiencing homelessness,” and although he acknowledges the need for change, his timeline is lengthy, and the break-up of the encampment continues. Although empathetic to those experiencing homelessness, the community is frustrated over the significant rise in violence, crime, and overdoses (Goulet, 2022; Pijl, 2020). The growing community resentment creates friction and a sense of anger or blame instead of rallying together to create change. The Lethbridge SCS had a six-month operating budget of $2.9 million dollars, which should be allocated to creating and managing Indigenous-led rehabilitation programs and safe housing (SCS Review Committee, 2020). Instead, the provincial government withdrew funding because of ARCHES’s gross criminal mismanagement of public funds and did not relocate the funding elsewhere to help Lethbridge’s vulnerable urban population (Kilpatrick, 2020). On a positive note, the provincial government promised $6.5 million dollars over three years to the Blood tribe to expand existing addiction treatment services on the reserve (CBC Calgary News, 2020). Although this is welcome support for the Kainai nation, it does not provide easily accessible support for the urban population.

Another underfunded program with the potential for change is the Harbour House, an emergency shelter for women, witnessing an enormous need for safe housing for women and children fleeing domestic violence. From April 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022, emergency calls or visits, 1,491 women sought shelter. The organization was able to support 171 women and their children, approximately 11% of the women in need. Of the 171, Indigenous women represented 109 of those receiving support (Tizzard, 2022). 89% of women seeking safety and shelter had to find another option, which may have resulted in homelessness or returning to abusive relationships. Many factors contribute to Indigenous homelessness, but if more culturally immersed programs are available and led with care and compassion, there is potential for immense change through referrals, rehabilitation, and policy change.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2012) appeals to the federal government “to provide sustainable funding for existing and new Aboriginal healing centres to address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual harms caused by residential schools.” Out of the many calls to action for reconciliation, twenty-one is a crucial request that requires immediate undertaking. Lethbridge Niitsitapi’ leaders are taking the initiative and creating Indigenous-led programs to begin the process of reconnection. Mark Brave Rock founded the SAGE clan, which stands for secure, assist, guard, and engage; they are a non-profit organization that patrols Lethbridge providing food, drinks, and friendship with the vulnerable population year-round (Sage Clan, 2019). They also participate in community events and aim to connect people suffering from addiction with treatment facilities. Their relationship-based outreach is more alluring to those who may feel alienated (Sage clan, 2019). Sheldon Day Chief founded another non-profit organization that focuses on at-risk youth. The Sweetgrass Youth Alliance “exists to make positive changes in the lives of all youth no matter where they come from or where they are going. We assist in the transition to adulthood and provide programs and activities to improve quality of life, especially for our most vulnerable youth.” (Day Chief & Jensen, n.d). They offer low-cost youth camps, opioid crisis support, charity work, and community services (Day Chief & Jensen, n.d). Both programs are relatively new; however, they have been part of successful diverse and inclusive outreach programs within Lethbridge. Day Chief sends the message, “it doesn't matter who you are, if you're struggling in the street, Sage program and Sweetgrass are there for you” (Marks, 2021). Day Chief, Brave Rock, and Clarence Black Water, Blackfoot community leaders, set up a tipi in Galt Gardens to share their message of assistance and plan to continue with it. Black Water wants his nation's population to know there is support for those who need it, and the tipi is a symbol and beacon for those experiencing homelessness (Marks, 2021). The invitation to engage with the community and receive help is inclusive, and their message of unity brings Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals together to create relationships and eliminate racism.

The Indigenous-led program I’taamohkanoohsin, which means everyone comes together, “targets an extremely marginalized and vulnerable population, primarily Indigenous people who are homeless, and nearly all of whom engage in substance misuse” (Victor et al., 2019). The program founders utilize Niitsitapi’ ways of knowing by providing food, drinks, and a judgment-free environment. Even under the influence of drugs or alcohol, individuals can come together as a community and eat, socialize, and participate in traditional Blackfoot activities (Victor et al., 2019). The program offers drumming, singing, storytelling, hand games, face painting, and most importantly, a safe space to be reintroduced to the cultural ways of the Blackfoot nations (Victor et al., 2019). An attendee of the program describes the program as a place to come and find peace, talk, and share your heart, spirit, and soul (Victor et al., 2019). These positive interactions lay the groundwork for coming together and reconnecting Niitsitapi’ people with Blackfoot culture, allowing them to establish their cultural identity, relationships, and positive self-esteem. The I’taamohkanoohsin program is a beginning step to healing and connection within the Indigenous population experiencing homelessness and substance misuse. These organizations and programs are similar in methodology, which creates a welcoming environment for those who feel alone, judged, scared, and hopeless.

In 2018, the first Canadian Indigenous-led urban land-based healing camp began in Yellowknife, NWT. Elder leadership and knowledge are at the core of the philosophy meant to bring healing to Indigenous groups (Redvers et al., 2021). Lethbridge could benefit from a similarly run program. Unlike biomedical-focused institutions that focus on the physical aspect of substance misuse and trauma, this camp implements traditional practices to aid in identity growth, connection, and healing to address the psychological and spiritual aspects of trauma. The site is located within the urban limits, allowing easy access for the urban population, and was built using traditional structures and materials to allow for a complete sensory immersion in traditional smells, tastes, sounds, sights and textures (Redvers et al., 2021). Traditional Indigenous foods, such as caribou, fish, whale blubber, and moose, are supplied whenever possible, alongside the integration of ceremonies, traditional food preparation, language revitalization, tool creation, medicine teachings, sweat lodges, and cultural gatherings. A key to the success of the program is the willingness of the leaders to meet the person where they are in their healing journey and work at that individual's pace (Redvers et al., 2021). Although the empirical data to support the camp's success is limited, the organization is unwilling to sacrifice the people's needs for data collection, and there is a surplus of positive feedback (Redvers et al. 2021). Similar programs in Canada and Alaska have reported an 84% or higher improvement rate among participants and a 58% decrease in child intervention cases (Allen et al., 2020). These decolonizing programs foster many of the cultural strategies Nutton & Fast (2015) outline in figure three. The city of Lethbridge would benefit from allocating uninhabited land for such a place, potentially along the Oldman River, where Niitsitapi’ can come together and learn their ways of knowing through living off the land and introducing traditions. There will likely be strong objections among non-Indigenous citizens; however, something must change. The cycle of blame, shame, and ignorance from some must be ignored for the greater good of the Niitsitapi’ experiencing substance misuse and homelessness. Tipis could be erected, creating safe and potentially semi-permanent homes for those in need. Constructing a culturally enriched encampment could bring a sense of community and safety. There is potential, but an assessment and probable alteration of city bylaws and funding is necessary to facilitate this solution.

Through the cultural immersion of Indigenous programs that aim to aid those recovering from homelessness, substance misuse, or surviving the foster care system, there is hope for a better understanding and respect of Blackfoot culture among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. The first step in healing is for all people to understand and respect the differences and values of Indigenous knowledge. Blackfoot knowledge understands the spirit as a separate entity connected to all creation, fostering wellness and resilience (Bastien, 2004; Victor et al., 2019). This connection is strengthened through ceremony, drumming, singing, smudging, face painting, and traditional dancing; these activities improve self-esteem and academic achievement among Indigenous youth (Nutton & Fast, 2015; Redvers et al., 2021). Children who grow up with a solid cultural identity show decreased behavioural difficulties or substance misuse, and greater resilience to historical trauma and racism (Nutton & Fast, 2015; Winters, 2019; Marsh, 2019).

Although non-Indigenous agencies and groups aim to create programs to help vulnerable people who experience substance misuse and homelessness, these programs often embrace an independent societal view on healing instead of an interdependent one (Katz, 2017; Bastien, 2004, Allen et al., 2020). Elders are integral in transmitting knowledge and cultural healing processes and must be supported to achieve what they know is needed for their people. Although the trauma cannot be undone or cured, a shift in perspective is needed when implementing a permanent solution, for the victimization of the Niistiapi' is unhelpful and irrelevant in the healing process. The Elders have the knowledge of their ancestors that is needed to bring balance, reciprocity, and connection to those who wish to reclaim their Indigeneity—teachings that encompass trust, sharing, respect, honour, and acceptance (Marsh et al., 2015). The support and advocacy of non-Indigenous citizens can create a future of friendship, trust, and mutual respect if everyone works together to change policy, attitudes, and healing methods. It is time for Lethbridge to take a proactive approach to support its Indigenous neighbours, friends, and families by embracing the Niitsitapi’ knowledge on an equitable scale and advocating for the creation of a land-based healing centre.

Alberta Children Services. (2013). Child intervention information and statistics summary. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/de167286-500d-4cf8-bf01-0d08224eeadc/resource/3ac3c113-1fae-49b0-b1cb-b77dcbadcdc3/download/child-intervention-info-stats-summary-2013-14-q1.pdf

Alberta Children Services. (2022). https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/de167286-500d-4cf8-bf01-0d08224eeadc/resource/25fac0d9-1fea-4a73-b7a9-08026b737aa9/download/cs-child-intervention-information-statistics-summary-2021-2022-q4.pdf

Alberta Government. (2017). Foster care handbook. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/c45f6b97-2e9b-43e0-90a7-f1788e5d8b25/resource/5f1183ba-a51a-4135-81d7-60e0d556469c/download/foster-care-handbook.pdf

Alberta Teachers Association. (2017). We are all treaty people. Walking together. https://empoweringthespirit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/PD-WT-17c_TreatyMap.pdf

Alberta Teachers Association. (2018). Numbered treaties within Alberta: treaty 7. Stepping Stones. https://legacy.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/For Members/ProfessionalDevelopment/Walking Together/PD-WT-16f - Numbered Treaties 7.pdf

Allen, L., Hatala, A., Ijaz, S., Courchene, D. & Bushie, B. (2020) Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CMAJ, 192(9), 208-216. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190728

ARCHES. (2020). “Who we are.” ARCHES: Your guide to Lethbridge queer health. https://archesqueerhealth.ca/who-we-are/

Bastien, B. (2004). Blackfoot ways of knowing: The worldview of the Siksikaitsitapi. (8th ed.) University of Calgary Press.

Belanger, Y. D. (2018). Ways of knowing: An introduction to Native studies in Canada. (3rd ed.). University of Lethbridge.

Belanger, Y. D., Awosoga, O. & Weasel Head, G. (2013). Homelessness, urban Aboriginal people, and the need for a national enumeration. Aboriginal Policy Studies. 2(2), 4-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.5663/aps.v2i2.19006

Brave Heart, M. Y. (2003). The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 35(1), 7–13. doi:10.1080/02791072.2003.1039998

CBC Calgary News. (2020). Blood tribe receives critical funding to expand addiction support program, policing. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/blood-tribe-addiction-funding-1.5484177.

CBC News. (n.d.). Interactive residential school map. https://www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/beyond-94-residential-school-map/

Coyhis, D. (n.d). Module 17: Addiction treatment, part b – specialized approaches for women & Indigenous populations. In Brain Stories Certification. Alberta Family Wellness Initiative.

Coyhis, D. (2011, April 6). The Wellbriety Movement and Intergenerational Trauma. YouTube. https://youtu.be/BqAqsrr9AnU

Day Chief, S., & Jensen, A. (n.d.). Mission statement. Sweetgrass Youth Alliance. https://www.facebook.com/SweetgrassYA/

Dryden, Joel. (2021). At Canada’s former busiest supervised consumption site, anxiety over what comes next. CBC News Calgary. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/lethbridge-supervised-consumption-site-alberta-1.6168733

Downtown Lethbridge. (2022). Safety. https://downtownlethbridge.com/content-detail.asp?ID=275&CatID=10

Fominoff, L. (2018). Safety concerns expressed by RibFest staff, organizers, and patrons at labour day weekend event in Galt Gardens. Lethbridge News Now. https://lethbridgenewsnow.com/2018/09/06/safety-concerns-expressed-by-ribfest-staff-organizers-and-patrons-at-labour-day-weekend-event-in-galt-gardens/

Fominoff, L. (2019). Lethbridge police say alleged assault in Galt Gardens drug-related. Lethbridge News Now. https://lethbridgenewsnow.com/2019/12/09/lethbridge-police-say-alleged-assault-in-galt-gardens-drug-related/

Goulet, J. (2022). City of Lethbridge responding to encampment concerns. Lethbridge News Now. https://lethbridgenewsnow.com/2022/07/06/city-of-lethbridge-responding-to-encampment-concerns/

Government of Alberta. (2021). Alberta opioid response surveillance report: First Nations people in Alberta. Health, Government of Alberta. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/ef2d3579-499d-4fac-8cc5-94da088e3b73/resource/8f1214fc-4db2-4e73-a297-1303293c4e90/download/health-alberta-opioid-response-surveillance-report-first-nations-people-2021-12.pdf

Government of Canada. (2022) First Nations child and family services. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100035204/1533307858805

Government of Canada Publications. (1978). Indian acts and amendments, 1868-1975. Consolidation of Indian Legislation, 2. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aanc-inac/R5-158-2-1978-eng.pdf

Hanson, B. L., Porter, R. R., Terhorst-Miller, H., & Zöld, A. L. (2020). Preventing opioid overdose with peer-administered naloxone: findings from a rural state. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0352-0

Hojjati, A., Beavis, A. S. W., Kassam, A., Choudhury, D., Fraser, M., Masching, R. & Nixon, S. (2017). Educational content related to postcolonialism and Indigenous health inequities recommended for all rehabilitation students in Canada: A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(26), 3206-3216. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00084174221088410

Katz, R. (2017). Indigenous healing psychology: Honoring the wisdom of the First Peoples. Healing Arts Press.

Kilpatrick, S. (2020). Kenney doubles down on pulled funding from consumption site in Lethbridge. CTV News Calgary. https://calgary.citynews.ca/2020/12/22/kenney-doubles-down-on-pulled-funding-from-consumption-site-in-lethbridge/

Labby, Bryan. (2017). Lethbridge police accused of ‘racist’ carding practices. CBC News Calgary. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/lethbridge-police-racist-carding-blood-tribe-1.4169754

Mahoney, A. (2018). Community in crisis walk to focus on local opioid crisis. Lethbridge News Now. https://lethbridgenewsnow.com/2018/03/05/community-in-crisis-walk-to-focus-on-local-opioid-crisis/

Many Grey Horses, D. (2021, August 1). Early this morning I was riding my bike to Starbucks. I saw a young man who didn’t look so good. [Status update]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/deloriamanygreyhorses/posts/10112322154171073

Marczuk, K. (2022). It’s not garbage to them: advocates enraged as homeless encampment removed near shelter. CTV News Calgary. https://calgary.ctvnews.ca/it-s-not-garbage-to-them-advocates-enraged-as-homeless-encampment-removed-near-shelter-1.5887266

Marks, S. (2021). It’s time for change at Galt Gardens: Sage Clan looks to push drug use out of downtown park. CTV News Calgary. www.calgary.ctvnews.ca/it-s-time-for-change-at-galt-gardens-sage-clan-looks-to-push-drug-use-out-of-downtown-park-1.5448456

Marsh, T. N., Coholic, D., Cote-Meek, S. & Najavits, L. M. (2015). Blending aboriginal and western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in Aboriginal peoples who live in northeastern Ontario, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, 12(14). 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-015-0046-1

Nutton, J. & Fast, E. (2015). Historical trauma, substance use, and Indigenous peoples: Seven generations of harm from a ‘big event.’ Substance Use & Misuse, 50(7), 839–847. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279961248_Historical_Trauma_Substance_Use_and_Indigenous_Peoples_Seven_Generations_of_Harm_From_a_Big_Event

Pijl, E. (2020). Urban social issues study: Impacts of the Lethbridge supervised consumption site on the local neighbourhood. Urban Social Issues Survey University of Lethbridge. https://opus.uleth.ca/bitstream/handle/10133/5672/Pijl-urban-social-issues.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Redvers, N., Nadeau, M. & Prince, D. (2021). Urban land-based healing: A northern intervention strategy. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 16(2), 322-334. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i2.33177

Sage Clan. (2019). Serve, assist, guard, and engage. SAGE clan. https://sageclan.ca/

Smith Sweetgrass, A. D. (2015). Feelings mixed at loss of former residential school. Aboriginal Multi-Media Society. http://www.ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/feelings-mixed-loss-former-residential-school

Statistics Canada (2022). Census of population. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm

SCS Review Committee. (2020). A socio-economic review of supervised consumption site in Alberta. Alberta Health Services, Government of Alberta https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/dfd35cf7-9955-4d6b-a9c6-60d353ea87c3/resource/11815009-5243-4fe4-8884-11ffa1123631/download/health-socio-economic-review-supervised-consumption-sites.pdf

Thistle, J. (2017). Definition of Indigenous homelessness in Canada. Homeless Hub. https://www.homelesshub.ca/IndigenousHomelessness

Tizzard, D. (2022). Personal communication regarding Harbour House statistics August 25.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2012). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

Victor, J. M., Shouting, M., DeGroot, C., Vonkeman, L., Brave Rock, M., & Hunt, R. (2019). I’taamohkanoohsin (everyone comes together): (Re)connecting Indigenous people experiencing homelessness and substance misuse to Blackfoot ways of knowing. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 14(1), 42-59. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v14i1.31939

Weasel Head, G. (2011). All we need is our land: an exploration of urban aboriginal homelessness. (Publication No. 896355904) [Master’s thesis, the University of Lethbridge]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/all-we-need-is-our-land-exploration-urban/docview/896355904/se-2.

Winters, E. & Harris, N. (2019). The impact of Indigenous identity and treatment seeking intention on the stigmatization of substance use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 1403-1415. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Impact-of-Indigenous-Identity-and-Treatment-on-Winters-Harris/37d1f2b6185b751bad45d2df329111c567e15b6b